All The Things Daisy Said

Make it stand out

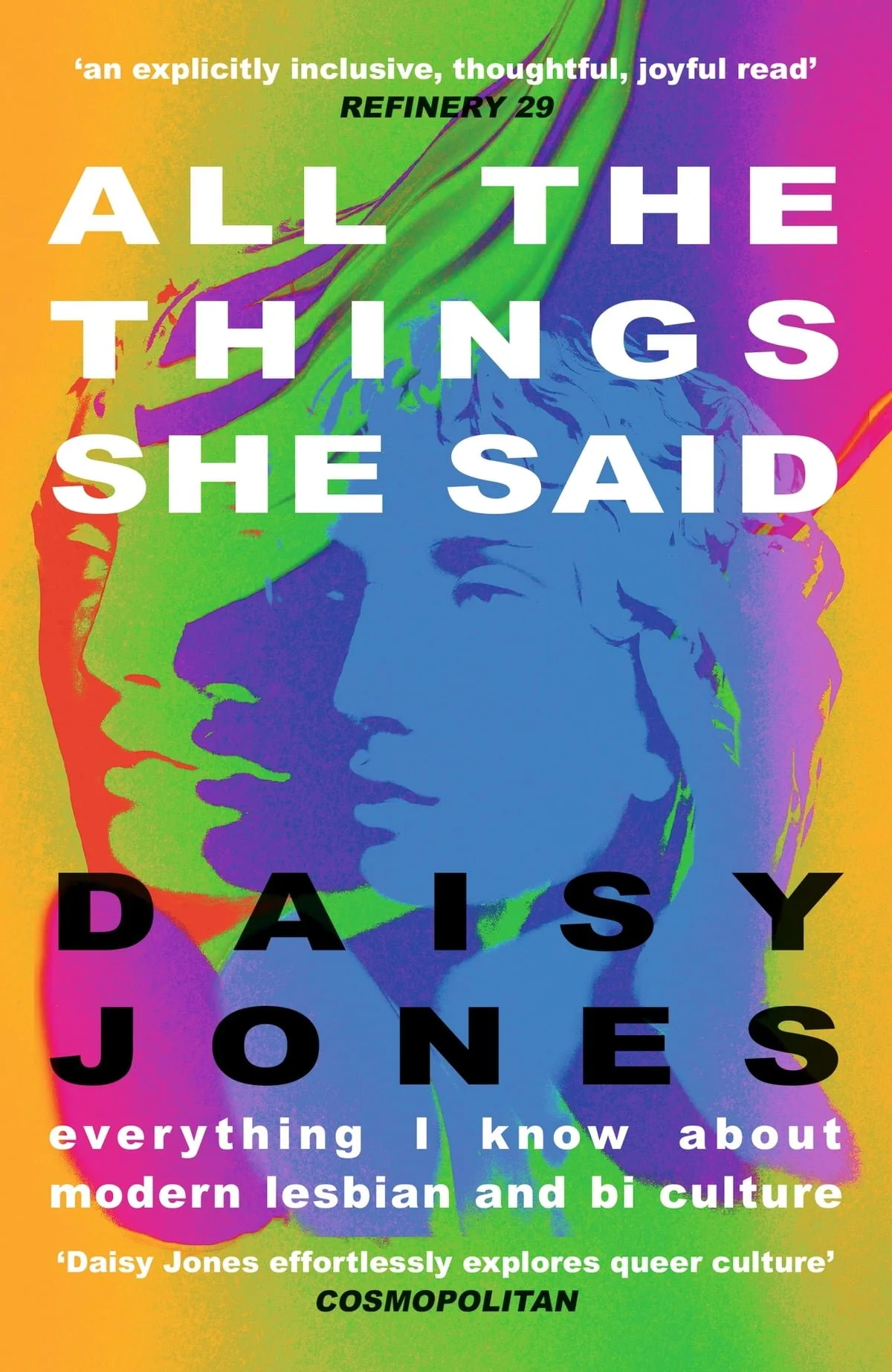

Sapphics, WLWs, gal pals, the list goes on of internet slang - derived from everything from memes to Greek poets - for referring to lesbian and bi people. It is undoubtable that the internet has revolutionised the ways in which we speak about our sexualities, but is it also responsible for changing queer culture itself? In her book All The Things She Said: Everything I Know About Modern Lesbian and Bi Culture, journalist and editor Daisy Jones interrogates current lesbian and bisexual culture in its many forms.

Both anecdotal and analytical, the book is a celebration of her identity as well as how young British people interact with queerness in the past decade. Our deputy editor Gina Tonic spoke with Daisy over email to deep dive into how a person puts together a book as exceptional as this one.

What inspired you to write All The Things She Said?

A few different reasons. Firstly, I felt like lesbian and bi culture was having a mainstream cultural moment and I wanted to capture that and also interrogate it. Before the 2010s in particular, it felt like lesbian culture was almost considered quite “uncool” outside of lesbian spaces, and being bi or pan was basically invisible or at least misunderstood. But now sapphic culture has become a lot more prominent on our TV screens, in films, on the runway, in major pop videos. So I wanted to zoom in on that recent evolution and explore what exactly happened.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

I also just wanted to write about something that I feel so tender towards. I wanted to write a love letter to queerness that exists outside of cis gay male spaces and culture. I view the book as a love letter in many ways.

The book talks about how the internet changed female queer culture drastically – do you think it has been a positive change or, in a different universe without the internet, queer women would have a better or easier life?

I think digital spaces have been monumental for queer communities. A lot of people I spoke to for the book – especially those in their late 20s or older – expressed how isolated they felt in their hometowns, or in more rural corners of the world, and finding platforms like Tumblr in the early 2010s completely blew the world open for them. For younger lesbian and bi kids, TikTok is a really fun celebratory space. They lift each other up. And obviously dating apps have transformed the way we find each other. Digital spaces can be an antidote to queer isolation, a way of connecting beyond the stifling physical realm.

“The way trans people are being excluded and villainised in the UK right now, for example, mirrors the ways in which gay people were excluded and villainised here in decades prior. It’s important to recognise the ways in which hate and distrust continually plays out and repeats.”

There’s a flipside to everything of course. Twitter can be hellish for example, and trans people especially are subjected to shit online all the time – not just from trolls with like 2 followers, but from lauded columnists, in mainstream publications, debating their existence, sat in their chairs at home. That side of the internet is gross and embarrassing. It will be a shameful footnote in the history of the internet.

There’s been a massive debate online regarding lesbian erasure through terms like queer, wlw, etc – what do you make of it and why?

I understand frustrations around being erased. It happens all the time. Lesbians have often felt disregarded within the wider queer community. But I don’t know if policing terms like “wlw” etc does anybody any favours. Those terms came about so as to be more all-compassing and inclusive and to make room for the multidimensional nature of sapphic identity. Plus, as I explore in my book, language changes and adapts and evolves continuously. One hundred years ago, for example, the word “lesbian” was used by doctors to describe what they deemed a “medical abnormality.” So yeah, I’m not a massive proponent of being extra about language, when so much of real experience is beyond language.

But that’s just my opinion. I can’t speak on behalf of all lesbians. I’m personally very chill about words. But that doesn’t mean the next person has to be, and that’s valid. I also don’t know what to call myself half the time! Today I might feel like a lesbian. Tomorrow I might feel like a genderless vapour who does not wish to be perceived.

Why is it so important for queer people to acknowledge the history of our culture?

For the same reason it is to acknowledge history more generally. To not make the same mistakes. To honor those who came before us, and fought for our rights. To have an awareness of how history often plays out. The way trans people are being excluded and villainised in the UK right now, for example, mirrors the ways in which gay people were excluded and villainised here in decades prior. It’s important to recognise the ways in which hate and distrust continually plays out and repeats. So we can look at current events and say, “hang on, haven’t we seen this before?”

Were there any topics you couldn’t fit in the book that you wish to be addressed? If so, can you give me some insight on them?

Haha this is a very good question and not one I’ve been asked before. By the time I’d finished the ten chapters or so, I honestly couldn’t write anymore. It was the middle of the pandemic and I was also working a full time job. I felt pretty burnt out. But there were subjects – art, sex, activism, zine culture, literature – which could probably have been turned into whole chapters. And lesbian and bi culture is so broad, that each of the chapters could have probably been turned into books.

Mainly though, I’d like more books from other lesbian and bi writers to be published and even more queer narratives on the page. More, more, more. Mine is just one small contribution, one limited perspective in a sea of experiences. Some of the best books of recent years have been sapphic – ‘Detransition, Baby’, ‘Girl, Woman Other’, ‘Milk Fed’. But I’m still not satiated.

The book talks lots about the important of club culture for queer people, but do you think the importance of the dancefloor still stands after a year and a half of pandemic life?

As long as the earth keeps turning, people will want to dance in a dark room and make out and get trashed. And as long as queer people still experience homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, racism etc, then those physical spaces will still remain integral as a place where people can actually let loose and feel free and comfortable in our own skin. Whether they will continue to exist post-pandemic is another issue entirely, but their importance is unwavering.

In the same vein, the pandemic has brought a lot of debate around the importance of celebrating pride (plus the commercialisation of pride itself) to the forefront, what do you hope a post-pandemic pride looks like?

I hope post-pandemic pride looks like a protest and a party. I don’t wish to see mega corporations with rainbow flags and banks and supermarkets espousing vague platitudes like “love is love.” That side of pride has no relevance to most queer people I know. I want to see LGBTQ people on the street demanding justice and also tonguing each other.

There is definitely an issue with queer spaces – particularly outside of London - where cis white gay men are prioritised and lesbians, bisexuals and other people in the LGBTQIA+ spectrum feel excluded where they are meant to be celebrated – have you encountered this and what would your advice be to anyone struggling with finding a home in typical gay venues?

I was quite lucky in the sense that I grew up in east London, so I didn’t experience that sense of acute isolation that can come from being in a rural town with one gay club 50 miles away. As a baby dyke I had options, so I feel thankful for that. But if you’re not so fortunate, or privileged, I’d say that there are other ways to find community. Most lesbian and bi people I know today met each other online, or through creative projects. Clubs and venues are just one way to “find your people.” Especially right now, when club culture isn’t what it used to be.

Another thing I would encourage people to do is: start your own queer night. Start your own queer night based on what you wish existed. Create your own utopia. For the book I interviewed a lot of people who run nights for queer people who aren’t cis gay men. And a lot of them said the same thing: it’s easier than you’d think. Just make it fun and people will come.

Words: Gina Tonic | Images: Daisy Jones + Jo Kiely