Art Rookie: Why We Need to Stop Taking Art so Seriously

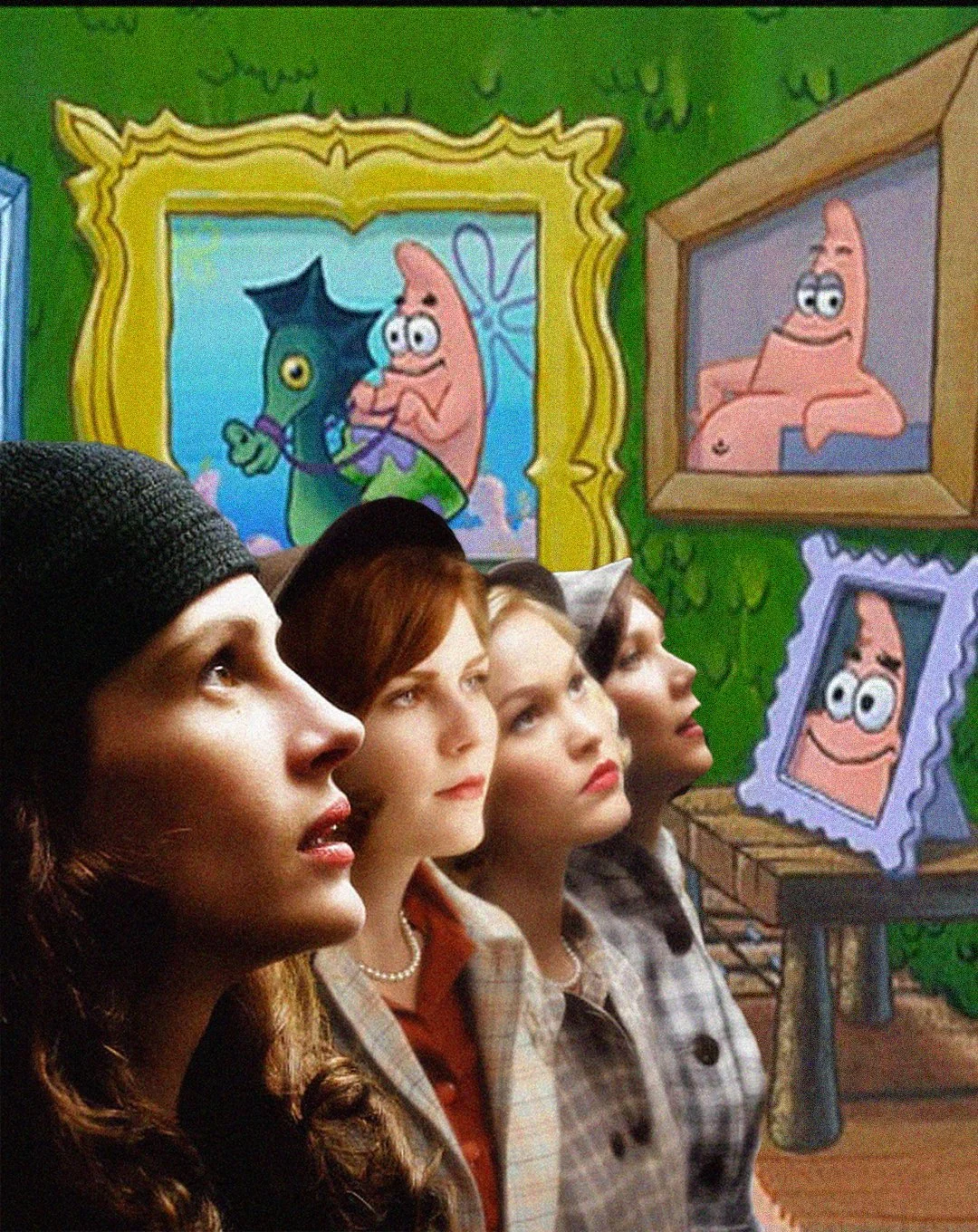

We're told that art is supposed to elicit a reaction. You're supposed to spend hours lost in the work of French impressionists. You're supposed to get (a word that people use as the defining factor as to if they did or did not enjoy works of art) why a Rembrandt is a masterpiece. If you don't get it, you're just not intellectually superior enough. You're just another one of those plebeians who doesn't understand art and never truly will. In the past, I wanted so badly to be Connell from Sally Rooney's Normal People when he stood in front of Vermeer's The Art of Painting for a whole day, transfixed by some divine work of genius the other less intellectual characters of the novel just did not get.

When I watched Mona Lisa Smile as a naive 13-year-old, I wanted to be Julia Roberts, the subversive Art History professor who "challenged" the status quo by praising Picasso instead of Michelangelo, who asked her students to consider art beyond the narrow definition of their textbooks. It may seem trite to admit these things as someone who will be going to uni to receive their official indoctrination into the history of art - I am convinced my offer of admission will be rescinded if the admissions committee hears of my pop culture pipe dreams. Still, it came from a place of wanting to close the gap between myself and "genius" and, in the process, gain footing in a world that actively rejects me.

I realised much later that what I was chasing was social capital. I had inadvertently subscribed to the idea that in the future, my refined taste and encyclopedic knowledge of high culture would drastically materialise into better connections, prestige and ultimately, a life that would mirror those of the one per cent. Pierre Bordieu, who coined the term, believed that people are not only defined by economic class but by any capital they have access to through social relations. It's a form of nepotism that goes beyond Hollywood. It's what networking promises you, the delightful melody to the tune of "a friend of a friend works there, and she could help you get work".

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

In Normal People, Connell's institutionalised social capital allowed him to close the gap between himself, his upper-class love interest, and Trinity's posh student body. Halfway through the storyline, his years of absorbing literature and art paid off in the form of a scholarship from college; his social capital transformed into real capital. Capital that then gave him the financial freedom to take his first European holiday and admire the Vermeer.

My desire to understand art was misguided; it came with expectations, the promise of inclusion in a world I thought would elevate my consciousness and grow my network of people. I wanted to regurgitate facts, know precisely what I was supposed to think at a show, to cross my arms in front of a painting at the National Gallery and for it to magically conjure something in me like the curators and critics promised me it would.

When it didn't, I would resign to reading the wall text, which was rarely insightful. In the comfort of my room, I would play catch up by reading the New York Times art section, watching documentaries on Youtube, and consuming PDFs of textbooks that promised a global survey of art. I wanted to bridge the gap between art and meaning. I wanted to have a visceral reaction to art, and I wanted to know how to respond to it.

Inspired by Bourdieusian ideas, I began thinking more deeply about why I attached more value to certain cultural artifacts than others. Why does it sound more impressive to declare you've read James Joyce or Joan Didion than it does to give five stars to a light beach read. To no surprise, it boils down to race and class, and while this seems obvious to point out, the taste of certain social groups, specifically the white upper class, are considered better as they confirm status and exclude those who don't have the knowledge that they accumulated through years of private school education and access to sites of "high" culture.

In 2017, the National Endowment for the Arts in America showed that the single biggest predictor of arts participation as an adult is exposure to the arts as a child. This statement comes as no surprise as our responses to different social environments are instinctively absorbed by us from a young age. It also explains the feeling of anxiety that we often feel in a gallery, like a fish out of water. But it is not just inbuilt tactics of self-policing that make us feel out of place in those spaces - galleries maintain these hierarchies of taste and upper-class values.

Arts institutions are often perceived, and rightfully so, as elitist. According to a survey by the Art Council in 2014, experiences within museums and galleries can be defined by levels of education, race, socioeconomic background, sexuality and even where people live. Depending on the space, these points of difference can prompt the viewer to be either more engaging or resistant to the work. Bourdieu expressed that the museum was "self-serving", an institution reinforcing cultural exclusivity by setting "agreed, but invisible standards of quality". Mainstream arts documentation in press releases, wall texts and magazines only reiterates this standard of "quality" and taints viewer experience by putting artwork into a hierarchy of importance.

Authoritative messaging tells us how to feel about art, rather than allowing us to have our own thoughts and our own personalised reactions to it.

These agreed-upon standards of visitor experience flatten our reaction to art; it categorises pieces into rigid criteria that must be checked off to be considered "good art". In the book Researching Visual Arts Education in Museums and Galleries, Maria Xanthoudaki shared their disdain for the role museums play in cultural exchanges; Xanthoudaki argues that "It is unclear for most visitors what role they should play other than that of passive recipients of expert knowledge."

It may be an over-generalisation to suggest this, but I think there is rarely room for us to have any real exchange with art, to derive meaning from the objects ourselves. We are cultural beings with subjective tastes; there are people in the world who dislike critically acclaimed tv shows, who don't get the hype behind Succession, for instance. Their opinion isn't incorrect - it's just that: their opinion. And while many may vehemently disagree (and take to Twitter by hordes to do it), at the end of the day, with many other forms of culture, especially pop culture, there is more room for debate, for a back and forth, for an honest discussion.

“Why can't the discussion behind artworks have that same freedom? Wouldn't it be more fun to actually consider paintings and exhibitions and honestly talk about how it makes us feel?”

A lot changed for me when I read Art on My Mind by bell hooks, who time and time again can be credited for shifting my perception of the world and for snapping me back into place when I am feeling particularly disillusioned. The book of essays published in 1995 feels just as relevant today. It opens a dialogue on the function of art and how the production and criticism of art can be revolutionary within the black community.

She writes, "We must shift conventional ways of thinking about the function of art. There must be a revolution in the way we see, the way we look. Such a revolution would necessarily begin with diverse programs of critical education that would stimulate collective awareness that the creation and public sharing of art is essential to any practice of freedom."

I was validated by bell hooks and Gabrielle de la Puente, and Zarina Muhammad of The White Pube, who have written extensively on their disdain for the traditional art world, to think more subjectively about my response to exhibitions, paintings, sculptures and all the other objects that I thought had inherent cultural value. I can now reveal my cards and admit everything I thought were "wrong things to say", like that I couldn't care less that the Mona Lisa was vandalised with buttercream. I think it finally made the piece relevant to me because all it was doing until then was being swarmed by visitors for a reason I couldn't put my finger on. I have begun to reject the myth of objectivity and have a real conversation between myself, the art, the artist, the curator and the critic.

To wade deeply into the world they have created for me and to proclaim my stake as an equal whose opinion is just as valid. A conversation between equals, not a brown girl in a dunce cap and a white curator with an air of self-importance.

Words: Zara Aftab