Barf Bags and Banana Stickers: Collecting Rubbish as a Subversive Act

Words: Maria Dragoi

Make it stand out

A few weeks ago I stumbled upon a Reddit subreddit called r/collections. I usually write about museums and I was looking for some strange institutional conglomerations - what I found instead was a litany of personal enthusiasts, sharing their hyper specific interests with each other, calling into the void and getting a response. I'd written about personal collections before, but only after they had been enshrined by institutions, sometimes several hundred years after their conception.

Something about the subreddit felt precious and immediate and I started to dig deeper. I've been asking myself for years what legitimises objects as worth collecting and where their agency lies. The answers to these questions are often contradictory and always loaded with histories of empire, colonialism, and possession. I thought, maybe naively, that online collecting communities might offer a different side to this coin - a way of reclaiming material culture.

I started by putting out a call for collectors of the strange and unusual and was surprised to immediately get a lot of engagement. Users started sharing their collections of whale figurines, empty deodorant cans, metal objects, shopping lists, and sugar packets. I'd posted my call out expecting some grittier stuff - I pitched this article with hopes of jars of toenails and locks of lover’s hair, but every reply I got back was incredibly enthusiastic about the mundane. Some collections were better than others. As soon as I had this thought, I knew I had to justify why I’d passed this judgement.

It wasn't necessarily about the quality of the objects, nor just about sheer quantity. It was really to do with the value ascribed to the ‘stuff’ by virtue of the aesthetics of its display. Collectors want their collections to be seen - the linked study found that display is part of the ritual of care performed by all collectors, and the approval of others online legitimises their amalgamation of objects. It's very similar to what goes on at institutions in terms of value creation. The object, once displayed, is stripped of its original value and given a new primary role as 'viewable'. After this swap, its original meaning may sometimes be carefully positioned back on top of it, but some collectors are more clumsy than others at doing this.

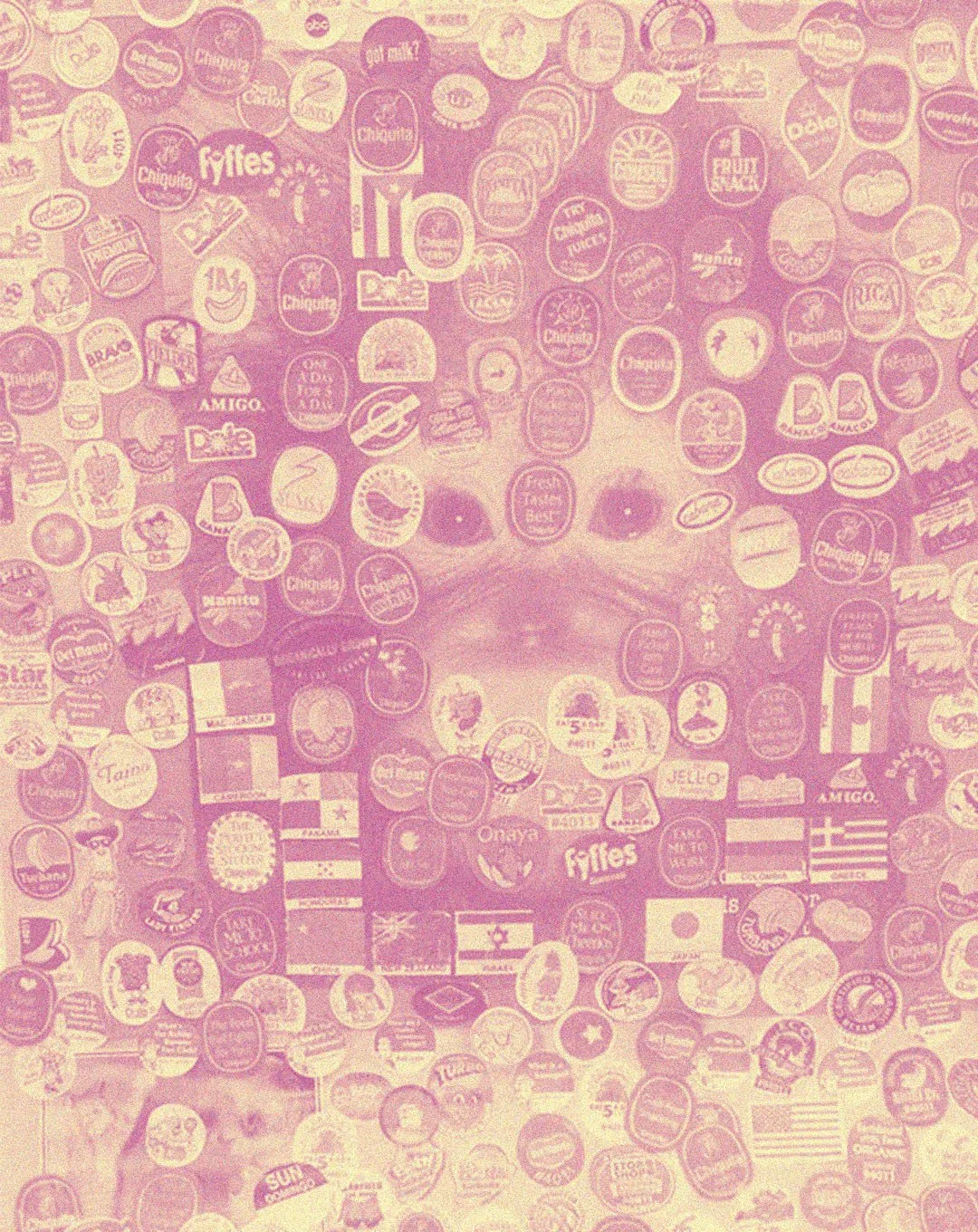

I began to think about the financial aspect of collecting ‘valuable’ things, and how value is determined by ‘belonging to’ a collection - usually an institutional one. The most interesting thing about the collectors on Reddit was their focus on collecting goods which were throwaways of our consumer culture. Becky Martz has collected 24,333 banana stickers. She also collects the elastic bands which hold bunches of broccoli together. Steven J. Silberberg collects airline vomit bags. Edoardo Flores has 20,711 'Do Not Disturb' signs from hotels. Each collection is meticulously researched, documented, preserved, and displayed. Trades and sales take place across the globe to expand the repertoire of each devotee.

It's very likely these people are world experts in their field. It's just an overlooked field, deemed lacking in cultural value by institutions. The appeal of sick bags, hotel door signs, and banana stickers is that they're free, small, and devoid of value to most people - which means less competition - and a likely willingness of friends, family, and strangers to help by saving the collector anything in this category they came across. Collectors build elaborate websites to display their treasures which are like virtual museums. Through the fastidiousness of collectors like Martz, the refuse of capitalist systems acquires new agency and value - it is reclaimed by the consumer.

“The appeal of sick bags, hotel door signs, and banana stickers is that they're free, small, and devoid of value to most people.”

This kind of collection re-defines materiality by changing something destined to be chucked into landfill into an important piece of culture without changing its physical makeup. It also throws a spanner into the conventional understanding of the envy-value of collections. To explain this better, let's rewind to the 15th century.

Rudolf the II of Austria is having drinks with some local nobles in his Wunderkammer - his chamber of curiosities. Here, he has amassed natural specimens, paintings, and manmade curiosities from around the world. The objects are one-offs, unique, irreproducible. They assert his reach and knowledge over the material world and reinforce his kingly status. This kind of personal collection, saturated in wealth and privilege, goes on to become the museum as we conventionally understand it.

The objects in museums are desirable because of their anti-ubiquity, their singularity. A collection of airline sickness bags is the antithesis. A commodity, manufactured in the hundreds of thousands, destined for disposal, is made desirable due to its belonging in a collective group. I never thought of keeping a Do Not Disturb sign, but suddenly, seeing Flores’ beautifully scanned photos of thousands of them on Flickr, I want a binder full. I begin to ask myself if I too should be a hotel sign collector. I start to look at the things designed specifically to be overlooked with fresh eyes. I begin to assign long term value to things in a material culture which begs me not to. I subvert.

It's not all sunshine and roses though, because corporations have cottoned on to the fact that collecting seems to be an innate human desire. There's been brilliant writing about collections of pebbles and shells found during archeological digs of neolithic sites. Banana companies like 'Chiquita' change their labels often, knowing a new release will enthuse collectors to buy their product to add the sticker to their collection.

The bad news for Chiquita is that anyone can peel a banana label off in a shop without buying the banana. In fact, most of the incredibly thorough personal collections are made up of the things you get given for free. It’s this re-assignment of value that’s radical. It's unclear whether the fanatic collectors who I've spoken about are aware of their subversiveness. Whether they’re conscious of it or not, this kind of collecting, and the digitisation and community engagement that follows, acts as an important guardian of a material culture usually overlooked by museums.