Bring Me A Dream: On Insomnia

Make it stand out

They say sleep is the cousin of death, but to me, it’s an estranged father or a guy that’s ghosted you – elusive, hard to pin down. I dream of dreaming, of shutting my lids and drifting to la-la land, waking only at the designated time. Reaching sleep takes a generous administration of Zopiclone, 37 position shifts, a poorly executed meditation session and a desperate plea to the gods.

I first experienced insomnia during Year 6 SATs; anxious about the next day’s exam, I tossed and turned as the arms on my dolphin clock raced to morning. I recall my mom running me a bath to relax as the sky cracked into apricot, and I sobbed. I would come to accept insomnia as a given in periods of high pressure and do my best to prepare – going to bed earlier, avoiding certain foods, no screen time after 9. But, as the effectiveness of each attempt failed, I realised that despite fastidiously controlling my environment, my insomnia was fuelled by outside forces.

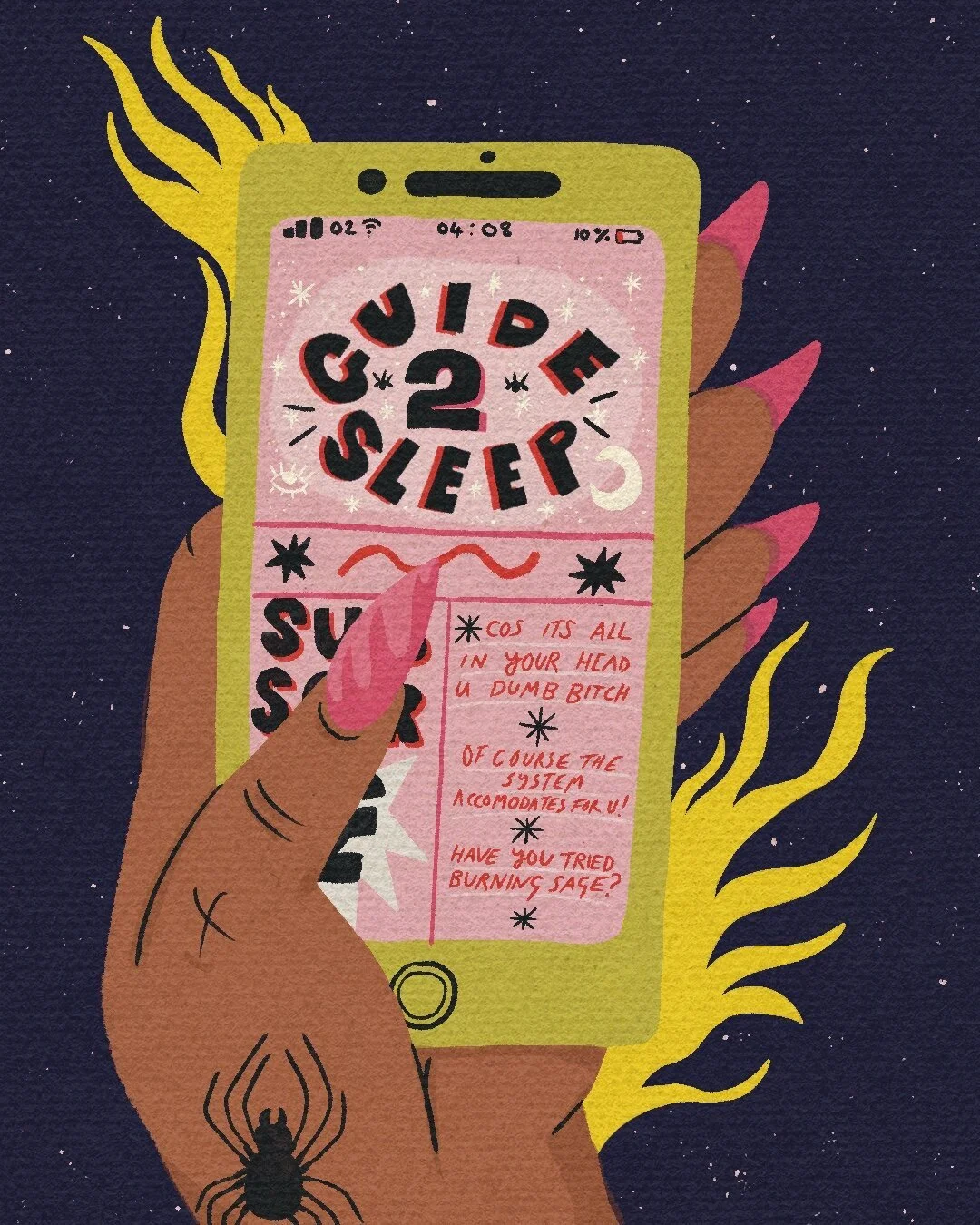

As I got older and the stakes grew higher (I could get fired!), the bedtime rituals and daily routines became so complex that Monday-Friday was an assault course of dos and don’ts. So, armed with a knapsack of homoeopathic remedies, I embarked on my personal self-help journey. Sleep tracking apps were my maps, valerian root my sustenance, lightweight pyjamas (to counter the weighted blanket), my uniform. I scrambled down the rabbit hole of self-help with the zeal of a Girl Guide.

In her latest newsletter, journalist Haley Nahman explores society’s focus toward “the magical thinking of the individual”, whereby “individuals can solve social ills through changing our habits or using modern tools and products.” I shuddered in recognition. My own self-help journey had obscured the real source of my insomnia, and the further I scurried, the harder it became to root out my malaise. I swallowed the dominant social discourse that favours individual actions – like quaffing Sleepy Tea – over social solutions – examining workplace culture, the competitive job market, unemployment, student debt, insert any number of issues keeping people up at night.

“Capital makes the worker ill, then multinational pharmaceutical companies sell them drugs to make them feel better,” writes Mark Fisher in his essay The Privatisation of Stress. Without solid social solutions, marketers fill the void (and suck up the profit) with aesthetically pleasing essential oils and meditation apps like modern snake oil salesmen.

Pounding lavender balm into my pressure points, dripping Rescue Remedy onto my tongue and spritzing my pillow became part of a manic nightly ceremony that ironically heightened my hyper-arousal, but to do nothing and wait for sleep ran contrary to popular opinion, worse still, it felt lazy.

My mom suffers from ME, which sits at the opposite end of the sleep disorder spectrum and where my insomnia is met with part admiration, part jealousy – “you must get so much done!” was a frequent response – hers incites disdain. You can’t put chronic fatigue to work. “Sleep is an affront to capitalism,” notes journalist Steve Poole in his review of Jonathan Crary’s book Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Once considered capitalism’s final frontier, sleep is no longer free of the constant distractions of daily life, the onslaught of information and the push for productivity. La-la land’s been conquered by the optimisation economy, and the price of entry is a Goop Sleep Chew.

When insomnia appears in the media, it’s often the catalyst to achievement – the journalist who launched her successful candle business in the wee hours or the other who wrote a book between stints of sleep. The list is endless but the subtext frustratingly similar – seize the opportunity.

When life gives you insomnia, make lavender candles. Their experience couldn’t be further from my own. I felt a husk of myself and floated through the days at a glacial pace while at night I’d squeeze my eyes shut and meditate to visions of purple, which is the kind of mysterious colour I associate with sleep. I’d envision Cadbury’s wrappers, the crystal ball emoji, Prince, gleaming geodes of amethyst and cling to these images like a blueberry buoy on an ocean of fizzy oranges, lemon sorbet and shamrock greens. I’d bob along like that sequence in Bart Sells His Soul where Millhouse, Martin, Sheri and Terry sail off towards the enchanted castle with their souls while Bart frantically paddles towards the space-age vista alone.

Lying in semi-sleep, purple pictures would wash over me until my mind would throw up the violent violet shade of my work Trello board causing tides of riotous colour to curl over my mind and spin me into waking life.

During these bouts of insomnia, my attention would splinter and shatter, and I’d use the shards to try to stab myself into action.

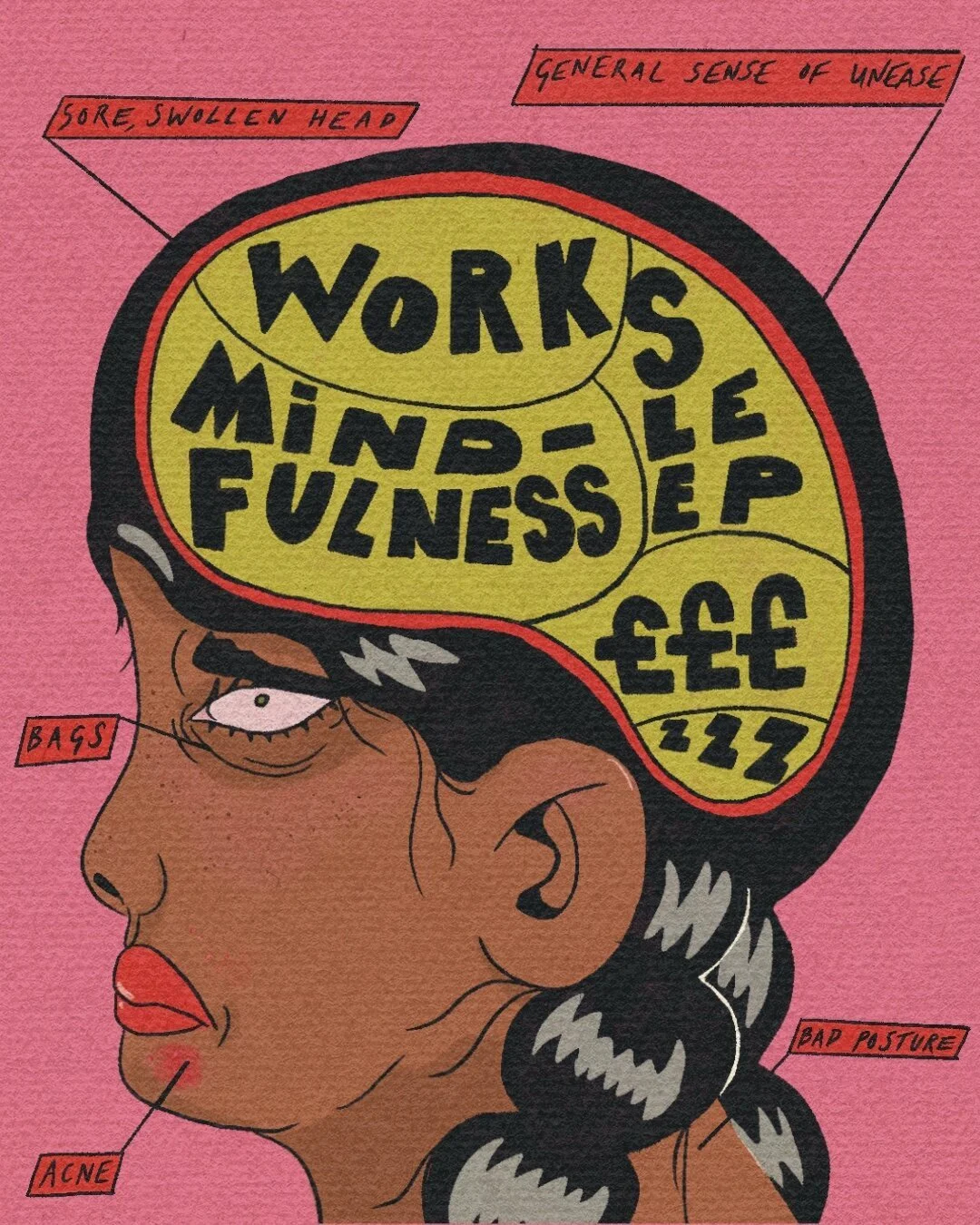

Our value system positions productivity as an indicator of purpose, which puts sleep – and the effects of sleep deprivation – as the antithesis of what’s revered. Colleagues would reel off a roll call of famous insomniacs and what they’d accomplished in their “extra” hours as if they’d been granted Bernard’s Watch rather than a medically recognised ailment. I fixated on the hours I could scrabble together to ensure a productive day’s work. I feared bedtime and relied on a smorgasbord of sleep aids.

In the book McMindfulness, Ronald Purser argues that mindfulness is a capitalist coping mechanism that places stress as a state of mind rather than the result of societal issues. Even good sleepers aren’t immune to the optimisation economy’s efforts to monetise our basest functions. You can always sleep better. Given that the mindfulness industry is worth an estimated £1 billion, there’s plenty of people invested in pushing the narrative that it’s all in our heads – but don’t worry, there’s an app for that.

“Fixing” my sleep took six month’s furlough and geographic distance from the place that was making me ill – two privileges granted under tremendously unique conditions (the pandemic). I don’t allow myself to consider what might’ve happened without that prolonged leave of absence; to do so would send me back to that bobbing buoy in a sea of acid colours.

In her closing argument, Nahman states, “we have, as a culture, over-invested in what are ultimately coping mechanisms, and have stopped imagining what it might look like for the harm to never occur in the first place.”

Words: Mischa Anouk Smith | Illustrations: Kate Gee