Culture Slut: Dissecting the 'Mean Gays' Trope

Gossip. We all love it. For some of us, it is one of the only things that makes life worth living, the only spark of joy in a dull, mechanical world, whether it’s about celebrities, your colleagues, or even just your friends. I was recently caught out gossiping about one of my very close friends, dipping my beak in things that were absolutely not my business but relishing every minute of it. I subsequently had to do a bit of self-exploration, a mini-journey of accountability and genuine apology, and honestly, it was eye opening. I freely admit that in my past (late teens/early twenties) that I was a Mean Gay, but I grew out of it as I got older and, hopefully, wiser, but I have also come to acknowledge that there is an eternal bond between gayness and a certain kind of cruelty which I’m going to explore in this month’s column.

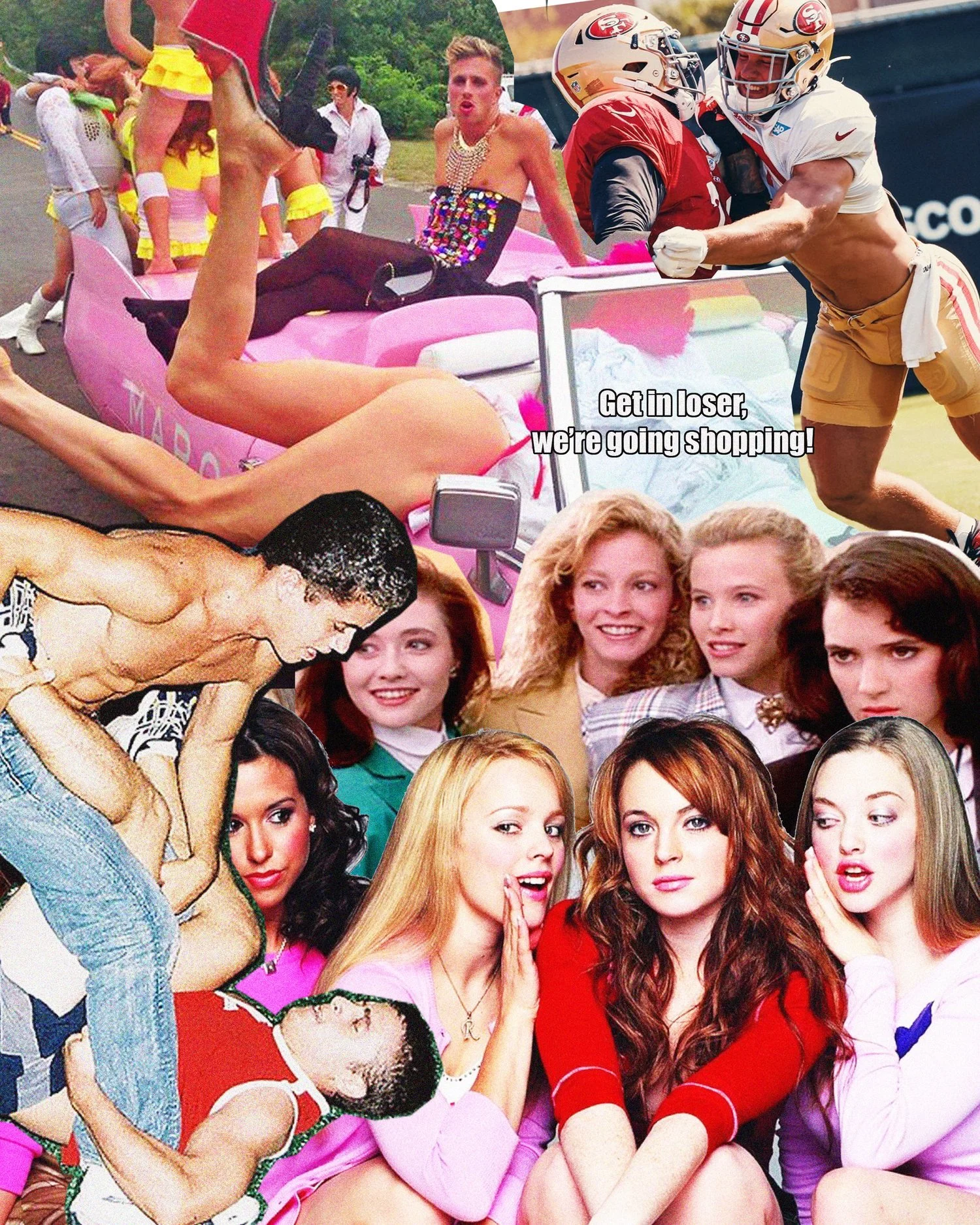

Welcome to the world of Mean Gays.OK, so I think we all know the Gay Best Friend trope, which was splattered all over 90s and 00s teen films and chick-flicks, the constantly-available-never-sexual-hilariously-witty-sometimes-mean side kick in films like Mean Girls and The Devil Wears Prada, gay male characters that were an open support system for the main girl, and little else. The defining characteristic for these roles was the comic relief they provided, memorable zingers, amusing but usually toothless nips at the heterosexual world around them. Every gay AMAB teen who grew up in the 00s will have been told by well-meaning girls that they remind them of Damien from Mean Girls NO MATTER WHAT they actually are like (I used to get compared to Maxxie from Skins, an athletic blonde dancer, whilst I was a miserable transvestite goth), and it’s because these early-modern representations of gays were the first that many teens would come across. Girls would be so pleased with themselves for having made this connection, for realising that this character was gay, and you were gay, so therefore, you were sympatico. I can assure you, the gay boys you said this to were not flattered.This gave rise to the less well known gay stereotype of Mean Gay.

It’s kind of ridiculous to call it less well known, especially now that TikTok has become a veritable encyclopaedia of character types previously ignored by the wider world, but for many years, Mean Gays were only famous in the gay scene itself. These were boys at the club who had had enough of being called Damien and decided they’d rather be The Plastics themselves, or The Heathers, or any other group of mean, elitist, fabulous girls that had been icons during their school years. These demon twinks thought they were the hottest shit in the club, laying claim to the best dance spots on the stage, the pool table in the gay bar (only when with lesbians), making friends with all the bouncers just so they can have anyone else ejected at will, partying at the same club three times a week, acting as though they were better than everyone else, and incredibly incestuous within their own group. These were the boys who would laugh at you for what you were wearing, who would throw drinks at their friend’s ex boyfriend, who would request songs at the DJ booth and always have them played.

I know about these boys because I saw them, and for a while I was one of them. The group I was in called ourselves the Glitterati (don’t even talk to me) and we went out every Thursday, Saturday, and alternate Tuesdays and Wednesdays. We were monsters, overly bitchy, completely stuck up, affecting the kind of mature-world-weariness that only 19 year-olds can. We were mean not only to people who tried to be nice to us, but also to each other. Gossip and rumour were like currency, sometimes completely fabricated, just to take a target down a peg or two, devious plots unfolding in real time whilst we sniggered into our vodka and diet cokes. We danced on stages in skinny jeans, drunk on our own self importance, newly confident thanks to our youth and beauty. This was a kind of anarchic way for many of us to hit back at the social hierarchy systems that oppressed so many gay kids in school. Finally, you were in a world where you weren’t automatically the butt of the joke, the bottom of the food chain. This was a world where you could be top dog, queen bee, the most popular girl in school if you ACTED like it, and how do popular girls act? Like Regina George.This kind of social performance has become a more prevalent in mainstream gay representations in recent years, such as the inclusion of mean gay Anwar in the bitchy school group in Netflix’s Sex Education, and the snobby David Rose in Schitt’s Creek. Instagram throbs with memes about Demon Twinks and West Hollywood gays, perfectly coiffed influencers prowling Pride parades and gay clubs. Drag queens like Violet Chachki and Gottmik make waves on YouTube by spinning their own brand of critical disdain that is then copied by every teen with an iPhone and a WOW Presents Plus account. This is all fine and dandy, but there is a deeper way that I’ve seen for the underlying resentment of social rejection come out in disenfranchised queers. Sometimes, there is a place for actual cruelty in gay friendships. It’s very difficult to explain, but I’ve seen enough glimpses of it in old gay films and books, and experienced it in some of my own friendships to know that it is very real.

“I think that this meanness used to be a lot more prevalent in gay circles, but as the world opens up and more and more people find freedom in expressing themselves, this defence mechanism becomes less necessary.”

It appears in some very close relationships and is part of the bond between participants, not serving as a barrier for emotional intimacy, but as a lubricant for it.From watching things like Drag Race, Priscilla Queen of the Desert, To Wong Foo, and you know, actually knowing gay people, we all know about the friendships that include making fun of each other, insulting each other’s clothes, taste in men, anything. We all know about playful shade, jokily picking at each other for fun, but often, I think this actually can run very deep, in a way that only queer people know. In fact, I’m going to go one step further, and say it’s only a thing that Faggots can understand. A Faggot is someone who has been called a Faggot on a crowded street in the middle of the day and not had anyone around them speak up. A Faggot is someone who has been so un-passable as a man, as a woman, as a straight person, as a member of “normal” society that they have had the experience of being singled out, of being shown cruelty. When we experience this harshness during our tender formative years, it becomes internalised as what many previous gay writers have called Gay Shame. It’s been linked to so many toxic gay subcultures; Masc4Masc Misogynists and Desperate would-be Assimilationists, but it is also present in a different way in the femmes and their flamboyant friends.

I think the kind of extreme cattiness displayed from AMAB femme gays has a psycho-social root in how they experienced school. I, like many other queers my age, found school difficult and lonely because of the innate feeling of being different, never fitting in fully with the boys or the girls, inhabiting an unhappy middle ground, both and neither at the same time. You were grouped with boys by teachers in single sex groups, which was horrendous, or you managed to join a gang of sympathetic girls who let you sit with them at lunch but you were NEVER allowed in to the inner sanctum of joining a sleepover. This leads to experiencing part of the socialisation both sexes stereotypically go through at school, mixed with your own potent toxic cocktail of sociopathy.

Boys usually strive to compete with each other, they implement social hierarchies by being the bravest, the most daring, the most stupid, seeing who can jump off the highest wall, who can say the worst thing to a teacher, who can be the most aggressive, who can deliver the most fatal blow. Girls work in more subtle ways, exercising their power in social manipulation and testing their own loyalties and those of their friends. If a problem occurs between best friends, direct confrontation is thrown out the window, one must say something to another friend who passes it on to another and then it finally gets back to the original offender, whilst creating constantly changing social atmospheres, either as punishment or as entertainment. Effeminate gay boys can take on the worst traits of all of these, the extreme daring and stupidity of boys mixed with the clever cunning of girls. Mean Gays don’t jump off high walls to impress each other, they don’t see who can drink the most vodka diet cokes, instead they see who can give the most vile put down, who can give the acid drop that not only embarrasses your best friend, but brings them to tears and forces them to seek validation from you.I had a best friend for many years, from about the ages of sixteen to twenty, whom I did everything with. We spent every day together, had a very intense relationship, and so much of our bond was built upon nastiness. We validated each other completely, intellectually bettered each other, learned from each other, created freely together, but its base was not in affirmations, but in acidic put-downs. We could argue happily for hours, in fact I remember one afternoon in our endless teenage years we staged a very dramatic and public breakup in a supermarket, accusing each other of the most heinous crimes, making such a scene that we were ushered out of the shop. We carried it on along the seafront, even when we no longer had any audience. I cried real tears of rage when he told me my acne scars looked like moon craters. One time I snogged his boyfriend at a party, so he punched me in the face. It was great. This playing with fury, with hatred and violence, learning how to utilise anger, gave a solution to all the pent up rage from a childhood of constantly being thwarted by the heteropatriarchy. To be honest it was probably a healthier outlet for my anger than my current methods, which is to ignore it or turn it inwards. Hm. I should mention this to my therapist, maybe.

A film that perfectly captures this kind of gay cruelty is Joe Montello’s The Boys in the Band, a 2020 remake of William Friedkin’s 1970 film, adapted from Mart Crowley’s 1968 play about a birthday party thrown by gay men. The text is incredible, and I vaguely remember having seen the original film in my youth, but watching the 2020 film on Netflix really hit home because I recognised myself and some of my friends in it. The film features nine men, all varying degrees of queerness (all played by gay actors) and their relationships to each other as friends and lovers. What starts off as casual fun and playful cattiness soon descends into harsh bitchiness and even abject cruelty. There is a constant threat of loneliness, isolation, anger at rejection from the world, love and friendship tainted with derision and self-hatred. One memorable line goes “You show me a happy homosexual and I will show you a gay corpse.”

Condensed, this sounds overly dramatic, but the reality of these pre-Stonewall relationships bowled me over, more than half a century after they were written. One couple fight over whether or not to have an open relationship, each spurred on by the terrible private belief that the other doesn’t love them as much as they need them to. The most effeminate gets away with some of the most poisonous barbs because they all know he faces the most degradation in their day-to-day world. One constantly lives beyond his means, overspending on clothes, on holidays, just to get away, just to run, and keep on running from a life of stillness. During the denouement, after the guests have spilled their worst, loneliest selves out for each other to see, the orchestrator of the party gets up to leave and delivers a vile, eviscerating speech to the host, then turns at the door and says “thanks for a wonderful time, I’ll call you tomorrow.”This one moment spoke to me more than anything else, because I knew it so well. This cruelty does have a place in some friendships, I’ve seen it in older queens, queens in bars spitting the most vitriolic poison at each other, yet never being seen apart. It’s the basis of every pre-Drag Race drag queen, hideous old men in bad wigs who can decapitate an audience member with a single joke. It’s in Charles Aznavour songs (the famous Comme Ils Disent, or What Makes a Man), it’s in contemporary 80s gay fiction (Mae West is Dead), its in the trans-American literary epic City of Night by John Rechy, It’s in goddamn Bette Davis films, which we all now know were feminised versions of gay male stories. Its taking the hostility of the outside world and transforming it into a bond with your fellow misfits, fellow Faggots.

I see it in some of my relationships now, in the subtle adult version of rumour spreading, not shouting lies over the music to the boys in the club, but in the deep meaningful conversations at after-parties, intimacy weaponised. I think that this meanness used to be a lot more prevalent in gay circles, but as the world opens up and more and more people find freedom in expressing themselves, this defence mechanism becomes less necessary. Being part of a well rounded, diverse group produces considerably less stress than being the only known queer for miles around. The stories I hear about secondary schools and their openness now sound a million years away from my experience, for which I am thankful. It's been a long time since I’ve been spat at on the street. It’s been an even longer time since I was slapped in a McDonald's for wearing a dress. The world is changing, and so too is our relationship with ourselves and our peers.

Maybe this self hate will die out in a generation or two, and all the queer youth will look back at these twentieth century gay texts and ask why do all these queers have to be so mean to each other? Why is there so much focus on loneliness and isolation, not friendship and camaraderie? Because there was a time, which now, thank God, seems to be long past, when I thought I would never have friends. That I never could because of who I was, and how the rest of the people around me saw me. All I knew was scorn, derision and belittlement. Those were the social interactions I experienced, so I absorbed them, internalised them, and adapted them to become part of my love language. Thankfully, as I’ve grown older I’ve learned healthier and more open ways of expressing my love for my friends, but even still, I can’t help but needle people about things, laughing at my friend’s bad dress sense (not even bad, I’m just being catty), happily complaining about so-and-so’s behaviour at the club last night, absolutely eviscerating someone at an after-party, reading them beneath the ground, then kissing them on the cheek and promising to call tomorrow. The world deserves to be a lot bit nicer, but for some of us, the Faggots, the misfits, the reclaimed, even cruelty can sometimes feel like kindness.

Words & Collages: Misha MN