Culture Slut: How the Films We Obsess Over as Teenagers Shape Us

Make it stand out

When you are a teenager, a single film can alter the whole trajectory of your life. At least, that’s what it felt like. I’ve written before about the magic of seeing midnight movies on television in your adolescent bedroom, and this is sort of a follow up; finding that piece of media that truly changes everything.

It is different for everyone, but can often be used as some kind of social mapping tool. I remember groups of girls in my secondary school finding themselves in the kooky French heroine Amelie (2001) - they emulated her haircut, her style, even citing her as the reason for pursuing languages in GCSEs and beyond.

It is impossible to overestimate the impact that Zack Snyder’s 300 (2006) had on teenage boys in the 00s, forming the base of every college and university rugby social for the next decade at least. For some it was the notoriously bloody Tarantino grindhouse homages like Kill Bill (2003) (proto-film bros), whilst others fell for the anti-establishment black comedy monologues of Trainspotting (1996) (burnouts who hadn’t even started to burn yet). Future horror buffs started with Naomi Watts in The Ring (2002), talking in hushed voices about how to get hold of the original Japanese version (bootleg DVDs, no streaming yet). A group of stoners from my school spent their weekends getting high whilst watching Soviet-era cartoons, well on their own path to the psychedelic exploration of personhood. For me and my friends, it was Velvet Goldmine (1998).

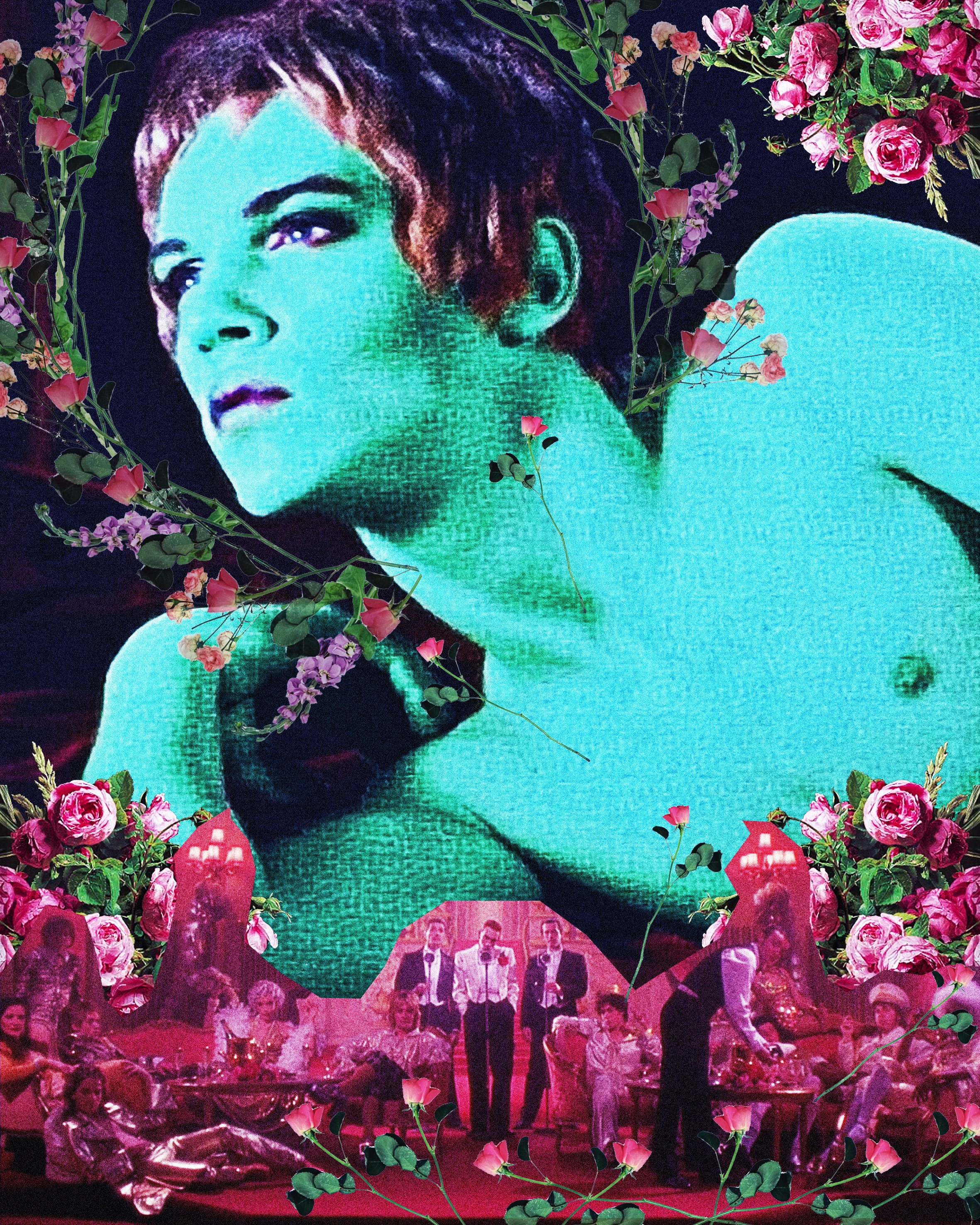

We were a group of goths who would hang out in the library at break times and talk about bands, boys and the secret gay internet that was blocked on any school computer and even on some of our home PCs. We were extremely dedicated to Brian Molko and the band Placebo, so when one of us saw a passing mention of them being featured in Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine, we made it our mission to track down a copy and watch it together. When we finally did, nothing would ever be the same for us again. Set in the 1970s, it follows the scandalous life of a bisexual glam rock singer and his outrageous affairs with men and women, his drug use, publicity stunts - all with a banging soundtrack featuring the likes of Lou Reed and Roxy Music. It had everything; gays, sad gays, pining gays, laughing gays, kissing gays, betrayal, nudity, cross dressing, sex appeal, orgies, humiliation, fabulous costumes, make up looks we could try ourselves, hairstyles we had never seen, it was total sensory fulfilment, both intellectually and in actuality. It was an exciting narrative filled with queer characters and situations that was still rare to find in mainstream media in the early 00s, but also provided us with enough material to daydream about for months to come in maths lessons.

“We were a group of goths who would hang out in the library at break times and talk about bands, boys and the secret gay internet that was blocked on any school computer and even on some of our home PCs. We were extremely dedicated to Brian Molko and the band Placebo, so when one of us saw a passing mention of them being featured in Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine, we made it our mission to track down a copy and watch it together.”

Velvet Goldmine showed us all our first on-screen penis, covered in glitter and attached to an exceedingly dreamy Ewan McGreggor, all long hair and black nail varnish, playing a sort of Iggy Pop-Lou Reed hybrid, rolling around on flaming stages in fits of ecstasy we could only dream of. Jonathan Rhys Meyers plays Brian Slade, a David Bowie-esque rock star with perfectly delicate features and delicious androgyny, Ziggy Stardust with better teeth and a modelling contract. It follows Slade’s coming of age in the 1960s and meteoric rise to stardom in the 1970s, lingering in the underground gay clubs of Soho, hypocrite hippie music festivals, New York rock bars, and lavish London town-houses. Toni Colette as Slade’s American party-girl wife is an absolute scene stealer, with the best wardrobe she’s ever been given in her varied career. The film is told mainly through flashbacks, as an 80s journalist tries to piece together the whole Slade story for an article, and this conceit allows the film to experiment in deliciously unexpected ways, from imagined BBC news reels, to stylised theatrical monologues and music videos, to scenes acted out by little girls with dolls, truly a melange of cinematic magic.

As a stand-alone piece, the film is great. Some things I still have issues with - there’s a weird bit about aliens, and I just can’t stand Christian Bale - but overall it’s a fantastic assault on the senses with lots of fun iconic moments and pop cameos. Yet this is only its surface level reading: the aspect that really makes this film an intriguing and essential piece of queer cinema is the thousands of threads it contains that link it to other important queer art.

First off, and most obviously, we have the story; a highly coloured fantasy about the possibly romantic relationship between Bowie and Iggy Pop, and Bowie’s rise to stardom through queer images in general, first emerging as an ethereal folk singer in a dress and eventually becoming the alien androgyne we all know and love today. We gain an understanding of Bowie through this film as a romanticised parody, but that’s not all. Much of the narration comes from the exquisite writings of Oscar Wilde and Jean Genet, queer authors that changed the world of literature and poetry forever. In a press conference, Slade and fellow rock-star Curt Wild fire off Wildean epigrams which are met with laughter and applause. Just before they kiss, they quote from The Picture of Dorian Gray: “The world is changed because you are made of ivory and gold, the curves of your lips rewrite history.”

The character Jack Fairy, described as the true original that all other stars stole from - a proxy for Little Richard and his outre queerness and performance style - floats around languidly, his cigarette “tracing a ladder to the stars” and espousing a thousand other Genet tropes and the poetic smut of Our Lady Of The Flowers. On that note, Lindsay Kemp, avant garde dancer, frequent collaborator to filmmaker Derek Jarman, early lover and mentor to Bowie, personal hero to me, appears as a pantomime dame singing a music hall song at the beginning of the film that inspires Slade to pursue a stage career. Kemp famously mounted a show of Genet’s Our Lady Of The Flowers in the late 60s that shocked the world with its outrageous sexuality and beauty.

Kemp is not the only underground queer icon to make a cameo in this film, the one and only David Hoyle is a scene stealer as Freddi, part of the Slade entourage that elevated him to superstardom. Hoyle is a cult cabaret artist, a drag horror that eviscerates the British bourgeoisie and materialistic hedonism. His dulcet tones are so recognisable that they cut through the musical montage he is presented to us in and you know immediately that he is someone.

All of these elements come together and quietly provide a catalogue of queer resources to any curious audience member struggling with unanswered questions. In an early sequence we see inside the Sombrero Club, a Soho gay bar, where a drag artist lip syncs to pop records and old queens converse in Polari. The exchange is comedically subtitled, under the assumption that the audience isn’t au fait with the secret language homosexuals used to communicate in a world before legalisation. Every part of the depiction of queerness in this film can lead you down a rabbit hole of cultural practices, icons and knowledge, and this example of Polari definitely had a hold on me. Polari had been a used as an effective tool on the fringes of British comedy for decades prior to this, most prominently by Kenneth Williams in the Carry On films and on his Julian and Sandy segment (How bona to vada your dolly old eek!) on the Round the Horne radio show, and is a foundation stone of our gay culture. It's one of the reasons that RuPaul will never truly understand the more elusive old school British gay humour, no matter how many seasons of Drag Race UK she does. Ooh, vada the omi palone, she’s dreadful, no lallies, no willets, no riah, just basket, gagging for a charver!

The effect this film had on me is unequalled. It gave me so much; it gave us lines of enquiry which felt empowering, rather than spoon-feeding us a toothless message of blanket acceptance, which in the end ultimately means nothing. Velvet Goldmine didn’t just endorse my social misfit status and leave it at that, it gave me the tools to grow. It gave me the writings of Oscar Wilde and practical applications for his epigrams. It gave me the mysterious figure of Jean Genet to research more and find my way into his literary world. It gave me Lindsay Kemp and David Hoyle. It gave me music, not just Bowie and Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, but Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music and Brian Eno and Jobriath and the Velvet Underground and all that came with them. It gave me Polari. Do teens still find films that give them so much? Or do teens have access to these things because they possess the entirety of the world’s knowledge on their phones already? Everyone needs guidance in taste, film will always play a role in that.

There have been a couple of films in recent years that have appealed to the teen still in me. 2022’s Please Baby Please, starring Andrea Riseborough (usurper of Viola Davis’ Oscar nomination last year) and Harry Melling (famous for playing someone unpleasant in Harry Potter), and a very camp cameo from Demi Moore’s newest face, is one of them. Melling and Riseborough play Arthur and Suze, a lower east side Manhattan couple plagued by a motorcycle gang whilst they go on a journey through gender and sexuality. The gang is styled in the fashion of Tom of Finland, the stylised lighting is very Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982) - another Genet story - and has some ironic dance sequences, but its dialogue is clunky and feels very remedial in its gender studies. Please Baby Please is interesting and has the potential to be a store of queer cultural knowledge, but it just doesn’t hit for me - though I accept I would have loved it in my youth.

The second is Postcards From London (2018), starring Harris Dickinson in one of his many gay roles, making him this generation’s Brad Davis. The film follows Jim, a young man with such excessive artistic sensitivities that he faints in the presence of great art. He runs away to London and falls in with a gang of male hustlers who dress up as famous works of art for their wealthy intellectual clientele; he tries to find meaning in an unfeeling world. Honestly, this film hits so many of my personal interests that it might as well have been AI generated just for me. I like this one more than Please Baby Please, but I guess it's because its format lends itself better to being a teaching tool for the audience. Jim learns about famous queer figures from art history and how they impacted our gay aesthetics and lives now, and thus so does the audience. It’s very niche, and very me, but ultimately not super-exciting if you aren’t into the premise straight off.

We all find ourselves in film, that’s why it endures as a medium. We are all the protagonists of our own dreams, but sometimes a little guidance is needed to bring us home. For some it's Enid in Ghost World (2001) waiting for the bus out of town, for others its Gerard Butler in leather underwear bellowing “This is Sparta!” For me it was watching the bullied little Jack Fairy painting his lips with his own blood and smiling at his reflection in the mirror knowing that, one day, the whole stinking world would be his. Ours.

Words: Misha MN