Dressing Dykes: Harlem's Power Couple, Edna and Olivia

Make it stand out

Have you ever heard of Edna Thomas? The most common answer to that question is probably “no”. I’d never heard her name until I read Saidiya Hartman’s incredible Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, where Edna appears among a cast hand-picked from the ticket stubs of Harlem’s history. Despite Edna’s name slipping to the sidelines, her legacy still takes centre stage; she was an actress, and part of the first generation of Black actresses making their names on the stages of New York City. She started her career with the Lafayette Players in the 1920s and gradually became a leading lady. Her biggest role was as Lady Macbeth 1936, and she appeared on the silver screen once, in 1951, as a supporting role to Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire. Photographs of her are housed in galleries and archives from the US to the UK. In almost all, she is in costume.

Edna was married twice: her first husband was a means to an end, an escape from the isolation of being a mixed race girl in an all-Black neighbourhood, a child who grew up thinking that her mother was her sister. Edna’s first husband was a drunk, and she was widowed by the age of 28. By 29, she was living in New York. She married Lloyd Thomas, manager of Harlem stars and began acting herself; her life was on the up. It wasn’t until the age of 41, however, that she felt passion for the first time. She was dancing with a woman at a party when, in her own words, “something very terrific happened to me - a very electric thing.” Clarity struck her: “It made me know I was a homosexual.”

Edna, in her stardom and her glory, was a catch. She’s described to have been beautiful and desired, with a “soft, deep voice” and “evident personal security.” It’s no wonder, then, that when notorious London lesbian Olivia Wyndham laid eyes on her, she was besotted.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Edna Thomas as Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, 1936.

Olivia was an aristocrat and one of the “Bright Young Things,” the decadent, eccentric, wealthy young people of Britain. She was 33 when she met Edna and her life turned around. It took 6 months for Olivia to win Edna over - Edna herself said that “I had avoided her because white women are unfaithful.” Despite this, Olivia repeatedly turned up on Edna (and her husband)’s doorstep, begging for Edna’s affection and dressed to the nines in tailored outfits. To Edna’s Harlem street, Olivia’s eccentricity seemed reflective of her Englishness rather than her lesbianism.

Despite Edna’s initial hesitation, the two fell wildly in love. Once again, we have a record of Edna’s own feelings for Olivia. About 5 years into their relationship, she said that “she has come to be very dear to me - not just for sex alone - it’s a very great love.” They lived together for decades, with Edna’s husband as a friend and housemate. The British press was shocked, but Olivia and Edna were used to shocking. They met at one of Harlem heiress A’lelia Walker’s lavish parties, after all.

A’lelia Walker’s parties were queer and opulent. Artists met aristocrats, singers met poets, people of all ethnicities mixed and made love to each other, and heterosexuality was not required. Clothes, too, were optional, but if they were worn they made a statement - A’lelia herself would walk around the rooms in a coordinating set made of expensive silk. Olivia and Edna were far from aliens in this environment, both of their lives entwined with the theatrical.

“Edna and Olivia were a power couple of Harlem in the late 1930s and for the rest of their lives. They brought two worlds together.”

Their stories are reflected in the garments that clothed their bodies. Edna came to life on the stage, her body the most her own when it was dressed to be seen by an audience. Saidiya Hartman, in Wayward Lives, captures Edna’s situation perfectly: “On stage [...] she was alive, resplendent. [...] She disappeared into other lives; she became other selves.” Edna spent her life looking for something greater. At age 41, when she discovered the thrill of women, perhaps she found it - but it still had to stay in the shadows. The world of parties and lingerie or performing in glittering crowns… these allowed her to be loud, at least for a little while. Edna Thomas was a successful, beautiful, Black lesbian, and though she didn’t realise who she was until later in life, she searched for it constantly in the roles she played and the costumes she wore. Edna the person and Edna the lover were completely tied to Edna the actress.

Olivia, similarly, searched for freedom in other-worldliness. Before she moved to America, she hosted her own parties at her flat in Chelsea, and was always elaborately costumed. In the 1920s, queer culture and the Bright Young Things had a penchant for sailor outfits, and Olivia never missed a queer trend: there are photographs of party-goers dressed in their best sailor looks in Olivia’s garden in 1929. This was a subculture, albeit one for the wealthy. It glistened just out of sight of the straight world.

Olivia Wyndham, 1925, by Berenice Abbott.

Edna and Olivia were a power couple of Harlem in the late 1930s and for the rest of their lives. They brought two worlds together. Even within these worlds, they individually contained multitudes: Edna was a wife and a successful actress, but also existed in an “electric” world where she danced with women and attended extravagant parties. Olivia was described in one newspaper as dressing in “plain, tailored clothes” and combing “her mixed gray hair straight off her wide brow”. Yet, she was the same person who begged for the love of a woman outside her front door and then gave her “the most exciting sex experience of [her] life” (Edna’s words!). Sometimes lesbian history is shaded and obscured, but hints of it - lesbian passion, lesbian fashion, lesbian talent and love - always shine through. This is history lit up by escaped light rays, like dust motes in a sunbeam.

A dinner party at the Thomases. Olivia is pictured second to left, Edna is in the middle (5th from each side). New York City, c. 1940.

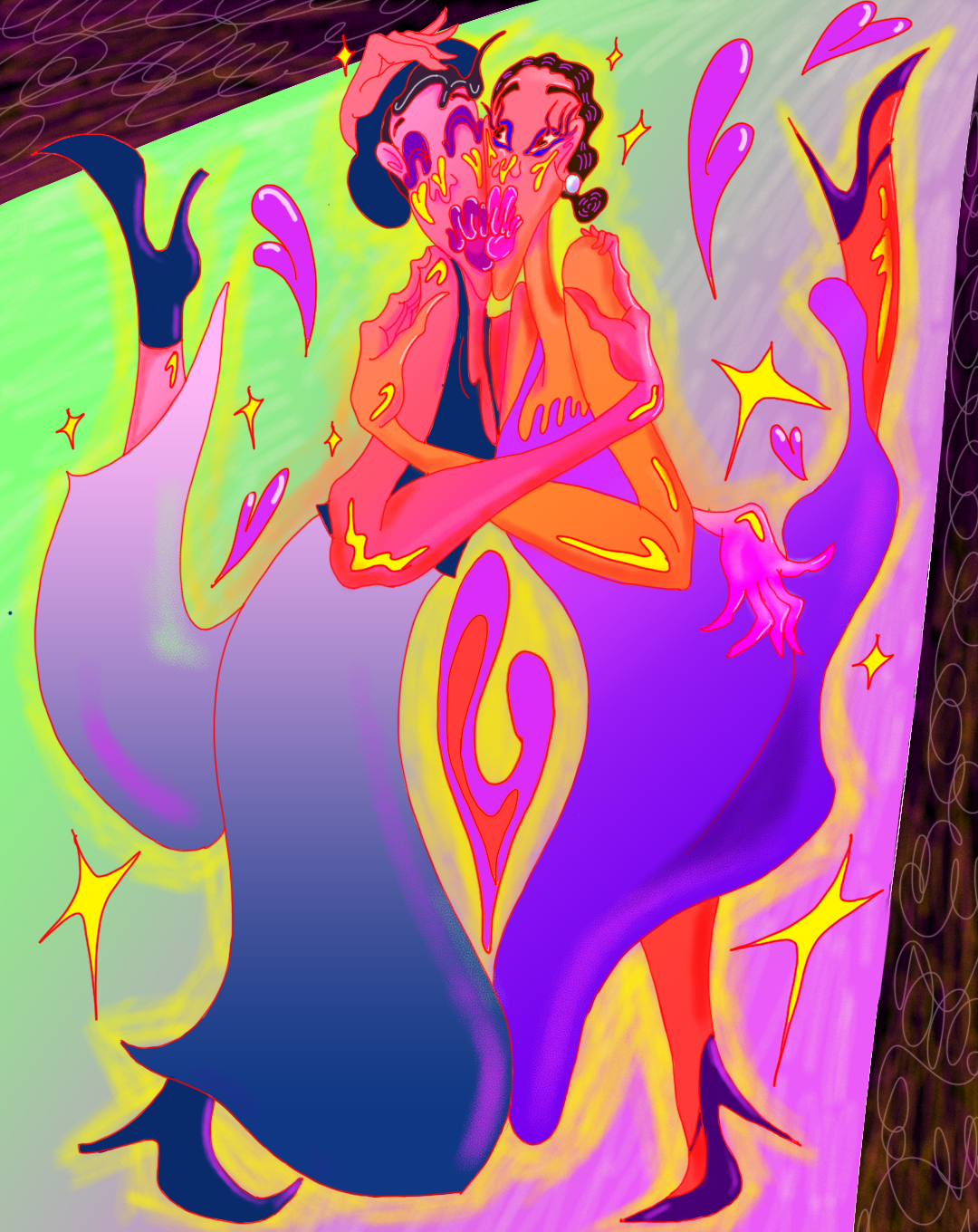

Words: Eleanor Medhurst | Illustration: Zoe Pham