Dressing Dykes: The Fashion of the Lesbian Sex Wars

The lesbian sex wars of the 1970s and 80s were… complex. On the one hand, there were feminists - often lesbian feminists - fighting for liberation, shouting back against male violence and criticising the misogyny of porn culture at the time. On the other were “pro-sex” feminists - again, often lesbians - who were also fighting for liberation, only from a different perspective. While anti-pornography feminists argued that porn normalised and reinforced violence against women, “pro-sex” feminists thought that no type of sex or sexuality was innately bad, and could in fact be a positive experience. They asserted that the patriarchy was the problem, not sex itself.

Both factions of the lesbian sex wars ended up, perhaps, simplifying reality. Andrew McBride, in an article on OutHistory (which you should check out if you want a more detailed analysis of the sex wars themselves), writes that “both camps became dogmatic in their ideologies and refused to see the complexities and intricacies of the issues.” This played out predictably - there was a strong distrust and dislike between anti-porn lesbian feminists and pro-sex lesbians. Because of this, the clothes worn by those on either side of the debate acted as uniforms and markers of difference. If someone was firmly in one camp, and dressed to prove it, there were certain lesbian spaces in which they couldn’t step foot.

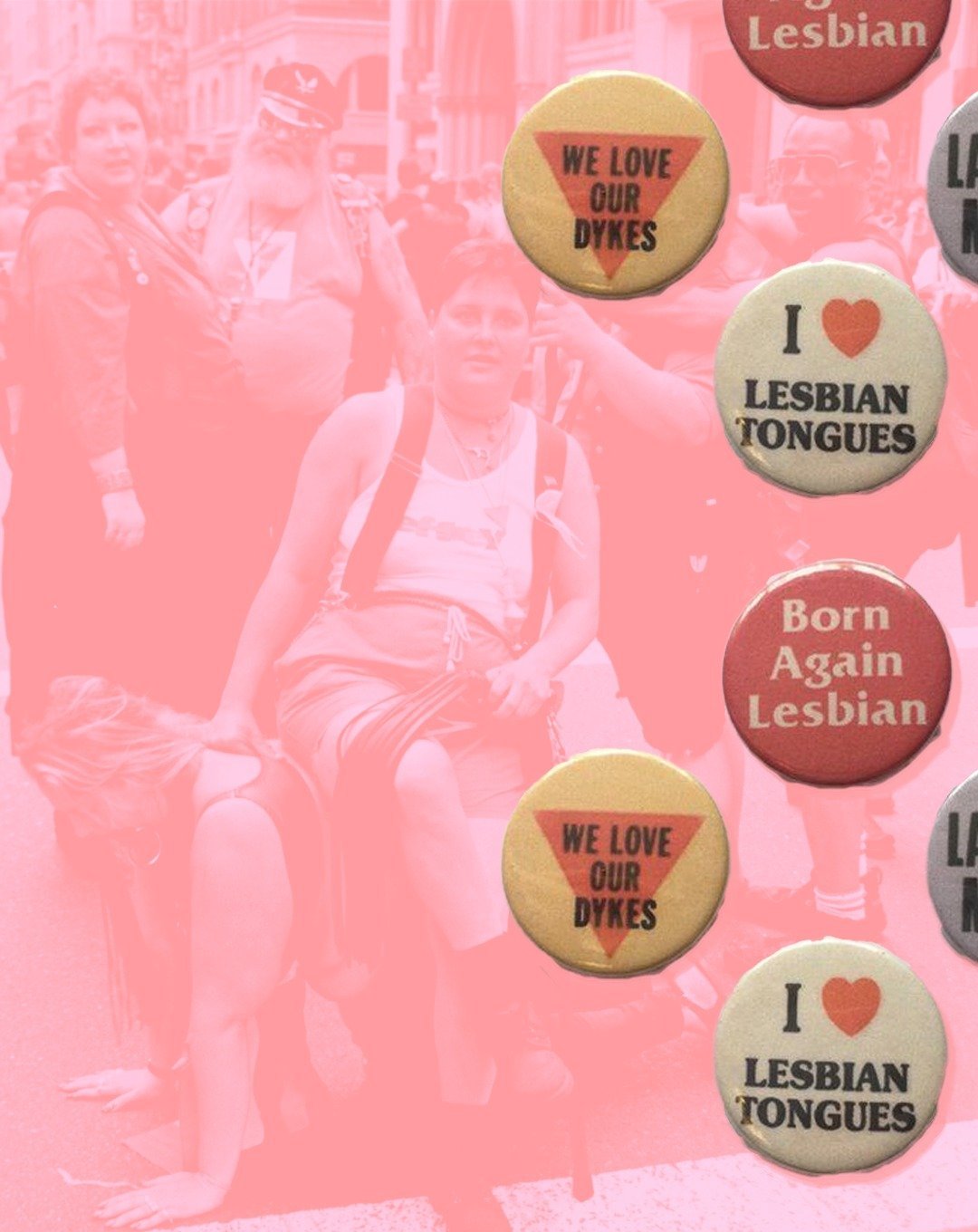

Bettye Lane, ‘Christopher Street,’ Christopher Street Liberation Day March, 1978, New York City. Catching the Wave, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The lesbian sex wars have been discussed back and forth for decades. Something that is less prominent in these discussions is how clothes were a vital part of the wars. The lesbian feminist dress code of the 70s and 80s was distinct. In the wider feminist movement the style became known as the “androgynous uniform,” but in lesbian circles it was the “dyke uniform.” Historian Betty Luthor Hillman describes that the style “often [consisted] of jeans, button-down work shirts, and work boots, often without makeup and bras, and sometimes with short hair.” It was practical. If the ultimate goal of lesbian feminism was freedom from gendered roles and the power heirarchies within them, then the dyke uniform translated this goal into clothing.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Lesbian feminists were embracing ideas of ugliness. They were women who would not dress to be desirable to men. Of course, a woman can wear any clothes she likes and still not be dressing for men, but it’s undeniable that embracing “ugliness” was revolutionary for the time. In Jane Traies’ 2018 book ‘Now You See Me: Lesbian Life Stories’, one of the lesbians that she interviewed , Silva, talks about how she found herself when she found lesbian feminist politics and aesthetics. She says:

“Of course, I got the gear, I looked the part. I cut my hair short, I didn’t quite have the dungarees, but almost. I looked like a lesbian, and all the women I was going out with looked like lesbians. They had short hair – and we didn’t wear makeup then, didn’t wear high heels. I’d been a very femme girl, very pretty, totally into clothes; and for me that was also part of it, because men always used to go for me because I was such a pretty girl. For me not to have to look like that, and still be a sexual being, was really important. I could cast all of this away and still be sexual, and there were other women like me.”

The aesthetics of lesbian feminism made Silva feel like she was no longer dressing for men. In fact, she felt the opposite: she felt like she could be desired by women. Silva, however, also noticed the negative side of the lesbian feminist uniform. It was lucky that she felt comfortable embracing the look, because if she hadn’t the community would have estranged her. In ‘Now You See Me’, she talks about this:

“Clothing is what we make it, and when we take it into our communities and our activist movements, we give it meaning.”

“I talked about those ‘lipstick lesbians’, and looked down on feminine lesbians [...] I remember in those days you could not wear a leather jacket in the GLC-funded Gay and Lesbian Centre and there was a huge separatist movement which I was on the edge of.”

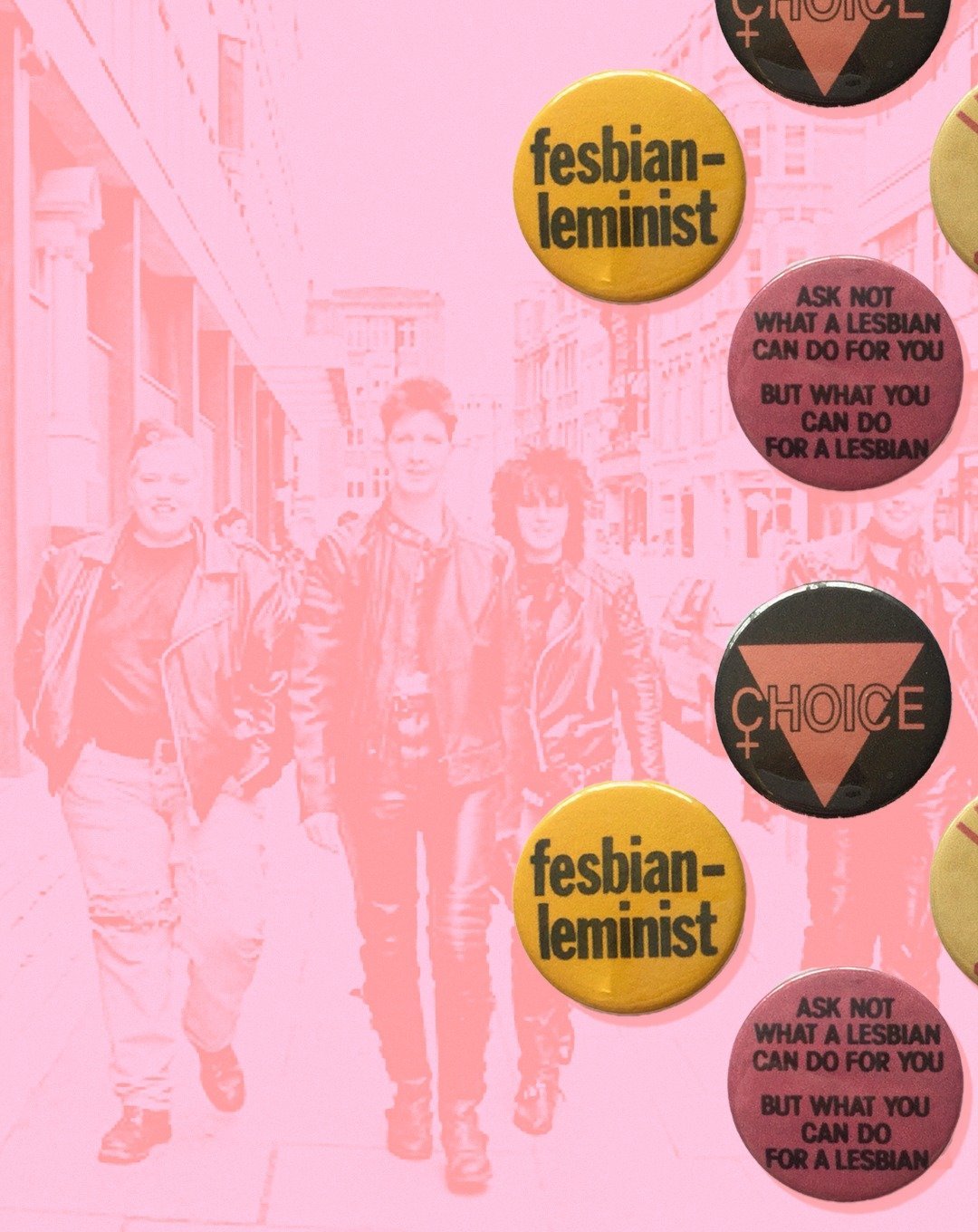

But wait - what’s this about leather jackets? Leather jackets were, essentially, short-hand for pro-sex lesbians - and not just pro-sex lesbians, but lesbians actively engaging in the kinds of sexual activities that lesbian feminists were against, like sadomasochism. Often, these lesbians were known as “SM dykes”, and a staple of their look was a leather jacket. Sabrina, a lesbian who was part of this culture in the 80s, told the Rebel Dykes History Project that she “wouldn’t leave the house” without her leather jacket, “whether it was winter, summer or whatever.” These individuals might have been outsiders to the larger lesbian movement, but they had spaces of their own in which they flaunted their style and their sexuality. In London, for example, there was music bar The Bell and SM club Chain Reaction, both of which were safe havens and sites of congregation.

The style of SM dykes wasn’t confined to just a leather jacket, though it was the most contentious symbol. Their entire outfit would speak to their political and community affiliations, literally from head to toe: their heads would be adorned with brightly-coloured hair or a partially-shaved “flat-top” style; faces and ears were covered with piercings; bandanas were tied around their necks; they wore heavy jeans or leather trousers, or sometimes a short leather skirt. They finished off the look with big, black, leather boots - known as army boots, since they were often from army-surplus shops, or “monkey” boots more colloquially.

The shoes on each side of the sex wars were probably the most unifying feature between the two groups - other than, of course, love for women. Big army boots like those worn by SM Dykes aren’t far removed from the practical boots worn by many lesbian feminists, often in the form of Doc Martens. This is symbolic, almost: though their lifestyles and their beliefs may have been very different, they were all lesbians, stomping out a new path for themselves and marching into the future.

In their own way, both sides of the lesbian sex wars made their mark on the world, on the queer community and on the women’s movement. Their clothing was rebellious. It was ugly and angry, practical and sexy, and those are words that can be mixed and matched to fit either side. Clothing is what we make it, and when we take it into our communities and our activist movements, we give it meaning. Sometimes, it speaks louder than our words.

Words: Ellie Medhurst