Dressing Dykes: The History of the Lesbian Drag King, Part 2

Make it stand out

This is part 2 of the history of the lesbian drag king: in part 1, we saw how drag kinging can be traced back to the 1700s (at least!), and my last column was a brief interlude on the legendary male impersonator of the Harlem Renaissance, Gladys Bentley. But what about more recent drag king fashion history? How did we get from the breeches-wearing women of the 18th century to drag kings as we know them today? The past and our present are linked materially, by commonalities in the clothes that adorn out bodies, and this is no less true for those who take to the stage in tuxedos and trousers, drawn-on moustaches and slicked-back hair.

Vesta Tilley, c. 1900. Published by Rotary Photographic Co Ltd. Donated to the NPG by Patrick O’Connor. National Portrait Gallery, London.

First, let’s make a pit stop at the music hall. Music halls were a phenomenon that rose to popularity in the 1890s - a period often referred to as the “Gay Nineties” (“Gay” being used to mean joyful or happy, but these 90s were also incredibly queer). The queerness of the time was reflected on its stages, and male impersonators were very much in fashion, particularly in Britain. While there may not be loads of evidence of actual, definite lesbians being male impersonators at this time, it was often very much implied; part of my work is to read between the lines of history, and the subtext here is hard to miss. In fact, the music halls of the Gay Nineties are so renowned that they were the inspiration for Sarah Water’s famous lesbian novel Tipping the Velvet. The main character of the book, Nan, begins a career as a male impersonator after falling in love with another male impersonator, whose glamorous on-stage persona opened a door for Nan that she never even knew was shut. It was an entryway into freedom: not just of sexuality, but of clothing. Though the story is about love and lesbian possibility in the late 19th century, it is also about the way that our clothing can shape us, and how male impersonators shaped themselves to the extreme.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

An obvious inspiration for Waters’ novel is Vesta Tilley, argued to be the most famous male impersonator of all time - understandable, since her career lasted from 1869 until 1920. Tilley, however, presented a very firm line between the male characters she portrayed on stage and her much more feminine reality. Though she went all in with her performances, even wearing male underwear rather than women’s corsets, she always wore fashionable, feminine dresses and bonnets when she wasn’t on stage. In 1890 she married a man who would later become a Conservative MP, Walter de Frece. There are numerous publicity photographs still existing of Tilley, and the divide between those of her in character and out of it is stark.

Tilley, despite not being an obvious lesbian, garnered a following of women whose sexual difference can’t be dismissed so easily. The way that she presented herself to the public, with her smart suits and confident posture, drew in women who - like Nan in Tipping the Velvet - had always been searching for something that was just out of reach. Though Tilley’s characters stopped existing when she stepped off stage, their influence remained. Women frequently sent flowers to Tilley’s various dressing rooms and repeatedly attended her shows; it’s not a leap to imagine that when they returned home, they might have stood in front of a mirror, trying on a father’s waistcoat or a brother’s trousers. Male impersonators introduced the queer women in their audiences to the idea that there was more than one way to live.

“Their costumes hung in wardrobes that are an archive and a runway all at once, a link to the past as well as the future.”

Vesta Tilley, of course, was far from the only notable male impersonator. Florence Hines is someone who we know much less about, but the lack of records is because of a difference in race and wealth rather than talent. Hines, whose career lasted from 1891 to 1906, worked in the US and was known as “the Vesta Tilley of Black male impersonators”. She allegedly took her stage clothes to the streets, which was an incredible action at the turn of the 20th century - trousers were very much not acceptable clothing for women, but if Hines got away with wearing them it was because she was a performer, and a well-known one.

Interestingly, although there are few records of Hines’ life or career, one that does exist is a public speculation of her relationship with a fellow performer named Marie Roberts. This appeared in The Cincinnati Enquirer in 1892, as recorded by historian Hugh Ryan. The newspaper wrote that “the utmost intimacy has existed between the two women for the past year, their marked devotion being not only noticeable but a subject of comment among their associates on the stage.” Hines’ love for women was far from a hidden thing and it was entirely intertwined with her job as a male impersonator. Her fame was what landed her in the newspaper and her job was how she met her lover, Marie, but being a male impersonator was also her protection, the excuse for wearing trousers or flirting with women. Being a drag king made lesbian self-expression possible without having to stick to the shadows.

There are other famous male impersonators, particularly in the early 20th century. One of these is Gwen Lally, who was an English male impersonator and pageant master (meaning that she led pageants, or dramatisations of historical events, a phenomenon that was popular at the time). Lally, like Hines, also took the masculine clothing of her performances to her everyday life - however, rather than being seen as rule-breaking, she was merely an eccentric. Her trouser-wearing was what set her apart, her unique selling point rather than a character flaw: she apparently claimed “the distinction of being the only actress who has never worn skirts on the stage", and even when she wore skirts off stage they would be part of a tailored suit. She was also, like Hines and unlike Tilley, recorded to have a female lover - this was another actress, Mabel Gibson, who lived with Lally for 40 years.

Gwen Lally, no date. Via King’s College London, kingscollections.org.

The first half of the 20th century may have been a prime time for male impersonation, but things evolved rather than waned as the mid-century hit. A prime example of this is Stormé Delarverie. Delarverie, who worked for a travelling cabaret called the Jewel Box Revue in the 50s and 60s, is also now known as the “Stonewall Lesbian” - the person who, after being clubbed in the face by a police officer at the Stonewall uprisings, prompted the crowd to fight back. She was as out of the closet as she could be, and her style always reflected that. I’ve written about Delarverie in my column before, but she deserves another spot here: she was a particularly notable presence in the history of the drag king, a drag king who was queer and loud and political, a real precursor to drag as we know it today.

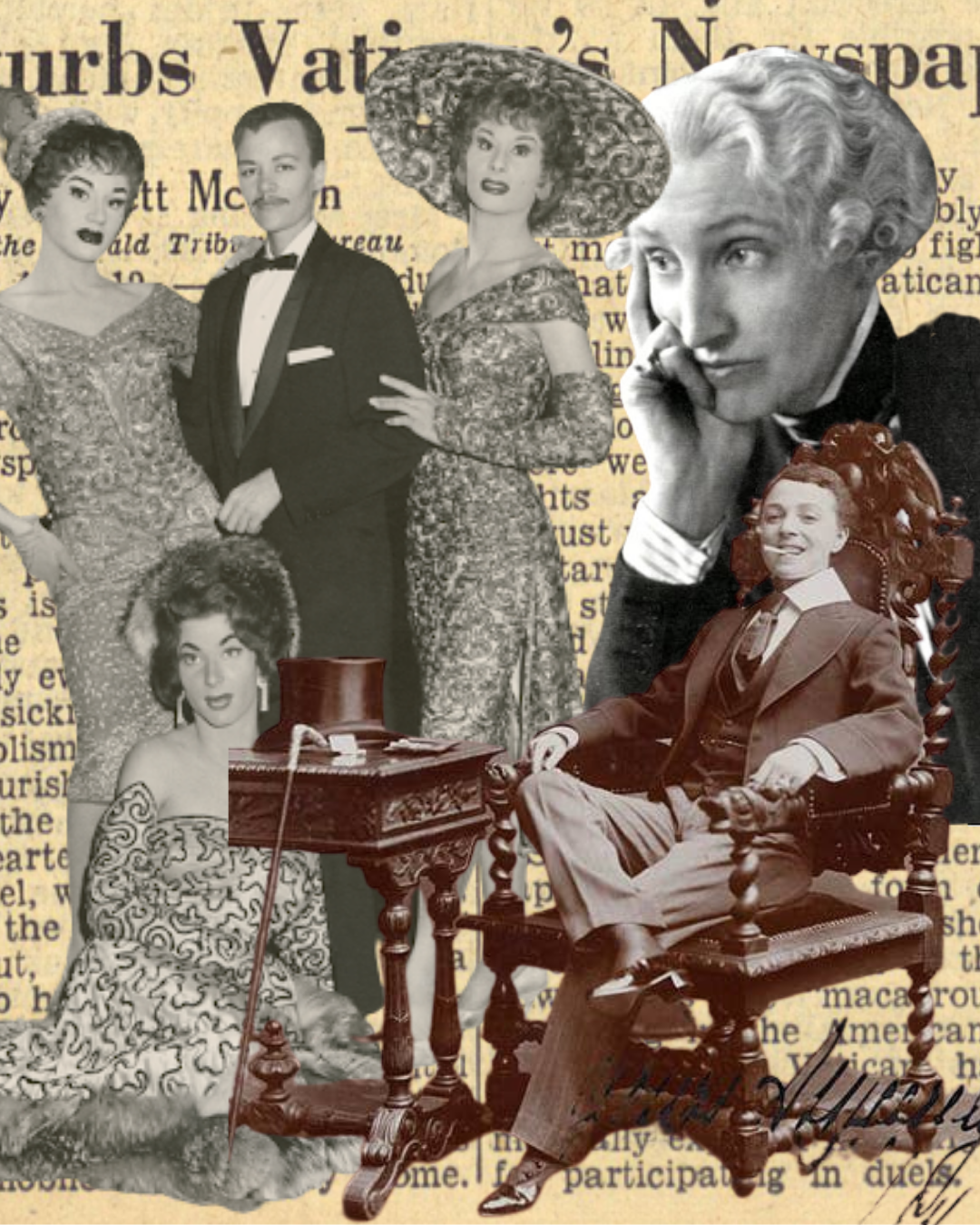

Stormé Delarverie and three female impersonators at Roberts Show Club, Chicago, Illinois, 1958. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Delarverie was tough, in and out of drag, but this toughness wasn’t all rough edges. It was hard, but it was glamorous; it exuded a message of “don’t mess with me” but it was also alluring. Delarverie made a living as a drag king, and she had to pull in the crowds with a slick moustache and a neat bow-tie. On the street, however, her look changed - the bow-tie replaced with a leather jacket, the moustache replaced with a cigarette. She may have de-dragged, but she never de-queered.

Stormé Delarverie exists literally decades and stylistically miles away from the likes of Vesta Tilley, with her Tory husband and her fashionable bonnets, but they’re both part of the same story. Drag kings have a legacy that stretches back hundreds of years, with centuries worth of trousers or breeches, adoring female fans and adoring real-life lovers. Their costumes hung in wardrobes that are an archive and a runway all at once, a link to the past as well as the future. It’s a story that’s still being written, constantly changing and evolving. Currently, drag kings are far less mainstream than drag queens, evident in the colossal Rupaul’s Drag Race franchise and its jarring exclusion of drag kings. There’s an alternative narrative to Drag Race, however, with drag king Landon Cider winning The Boulet Brothers’ Dragula in 2019: drag kings are definitely not going anywhere without a fight. Their craft has strong roots, entwined with fashion history, but also with performance history; with queer history; with history.

Words: Ellie Medhurst