Do-Nothing Feminism and the Documentation of the Banal

Make it stand out

If you are a TikTok user, it is likely you have had ‘I think I like this little life’ ringing round your skull recently. The earworm is the backing track to the “little life” trend – a viral format where young, mostly female creators interweave vignettes from their daily lives. The flawlessly curated montages often portray the same activities: getting coffee, going to Pilates, picnicking with friends, reading, eating, cleaning – banal practices that, in any other space, wouldn’t garner as much attention.

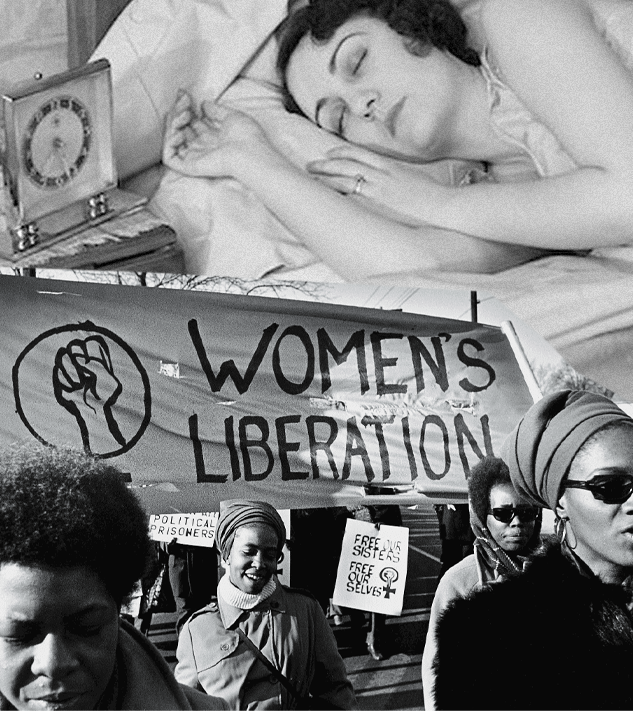

Trends like this are precisely what social media was designed for – a way for the average person to let others in on what they get up to day-to-day. It is true that most people’s lives consist of dull activities like getting coffee, cleaning, eating. It is also true that these acts are anything but revolutionary, so why are they being presented as such? I am calling this phenomenon “do-nothing feminism”, and there is no more accountable a figure for its emergence than British feminist author Florence Given.

With blonde hair and model-looks, Given has been hailed as “the voice of Gen Z”, earning accolades like Cosmopolitan UK’s Woman of the Year Award in 2019. Her debut best-selling book, Women Don’t Owe You Pretty, cemented Given as a leader in the gen z feminist literary canon. With cutesy illustrations and a bolshy hot pink-colour scheme, this how-to guide was held as gen z’s entryway into feminism, just as Naomi Woolf’s The Beauty Myth was for an earlier generation. Though it’s not her writing that earns her so much attention, it’s her aesthetic.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Her pink-themed Instagram page best encapsulates this. The page consists mostly of short videos of her morning routine, always commencing with the same exclamation – “good fucking morning!” Dressing her slim white body in flamboyant 70s clothing and red lipstick, Given leaps and sways around her spacious London flat, pouring coffee from a Smeg machine into a leopard-print teacup as she begins a day of “romanticising her own life”.

Much like the “little life” videos, Given does nothing in these videos – nothing remarkable, anyway. But with the help of expert producing and a keen aesthetic eye, banal activities are transformed into something aspirational, feminist, even. Given presents her daily choices as the acts of an empowered, independent woman. This phenomenon has a name – Choice Feminism.

Coined by Linda Hirshman in Get to Work: A Manifesto for Women of the World (2006), choice feminism characterises every act a woman performs as an inherently feminist one, simply because a woman is doing it. This not only individualises a universal cause, but also assumes that women have freedom of choice – a fallacy under capitalist patriarchy.

“Feminism is a universal, political movement. Collective action and social justice requires work – both physically and within oneself.”

It is interesting to consider that the practices depicted in these videos are often forms of aesthetic and physical upkeep, like “clean” eating or getting a fresh set of acrylics. A quick scroll on TikTok or Instagram reveals countless daily vlogs featuring activities of this kind, like this one or this one, as well as celebratory comments of the same tone: “girlboss” “slay” “inspiring”. The prevalence of these videos discredits the notion that these acts are wholly individual choices – is it simply the latest tactics by which women uphold expectations imparted by patriarchy to look a certain way?

But even if these practices were done out of personal enthusiasm, that still does not make them feminist in and of themselves. Presenting them as such not only bolsters Hirshman’s argument, but reduces feminism to nothing but an aesthetic trend – a cause entirely about optics as opposed to actual work. There is nothing wrong with “romanticising your life”. So too is there nothing wrong with doing nothing – rest and self-care can be revolutionary acts. But doing it under the guise of empowerment seems a cop out. It is especially egregious when it is presented as subversive – something thin, white, and wealthy participants of the trend, like Given, often do. Romanticising quotidian tasks by wearing an ostentatious outfit is fine, but it is not breaking the mould. To cast it as such is not only presumptuous and reductive, but also the ultimate expression of privilege.

Feminism is a universal, political movement. Collective action and social justice requires work – both physically and within oneself. Indeed, effective feminism places universal emancipation above individual liberty. Choice feminism perpetuates archaic stereotypes of the interests, hobbies, and abilities of women.. Now, mocking the ‘little life’ trend, and the trend of self romanticisation, has become a trend in itself. The same ideas that this content is trying to dismantle are being upheld - an attack against earnest solidarity isn’t exactly feminist either when critical thinking is eschewed for belittling one another.

That said, to suggest that by living their “little lives” gen z women are somehow brave feminists worthy of celebration is as patronising as it is reductive. Characterising the romanticisation of the banal as feminist is thus not only a lazy, self-serving form of activism, it enforces the need for women’s lives to stay “little”.

Words: Bridget Clarke