How Stardoll Shaped a Generation of Queer Kids

‘Does playing with dolls make you trans’ I erratically google on a Thursday night as I find myself reflecting on my gender journey and wondering whether my love for sissy games growing up was instrumental in my transness. Despite my search holding the tone of a concerned parent questioning at what point they should be alarmed by their child’s gender defiance, the answers fascinate me.

One result actually is from an apprehensive dad who has an eight year old sports-loving boy-things-doing son but who simultaneously is found playing with dolls – ‘is he gay’ stressfully asks the father on Tampa Bay Times. The expert agony aunt appreciates the concern and quickly reassures the parent and clarifies that ‘plenty of boys who play with dolls are heterosexual.’

Another result slaps readers with a sensationalist title: ‘New Study Suggests Playing With Dolls Proves A Boy Is Transgender’.

A Quora thread on whether ‘all trans women played with dolls and make-up when they were young’ immediately disproves that.

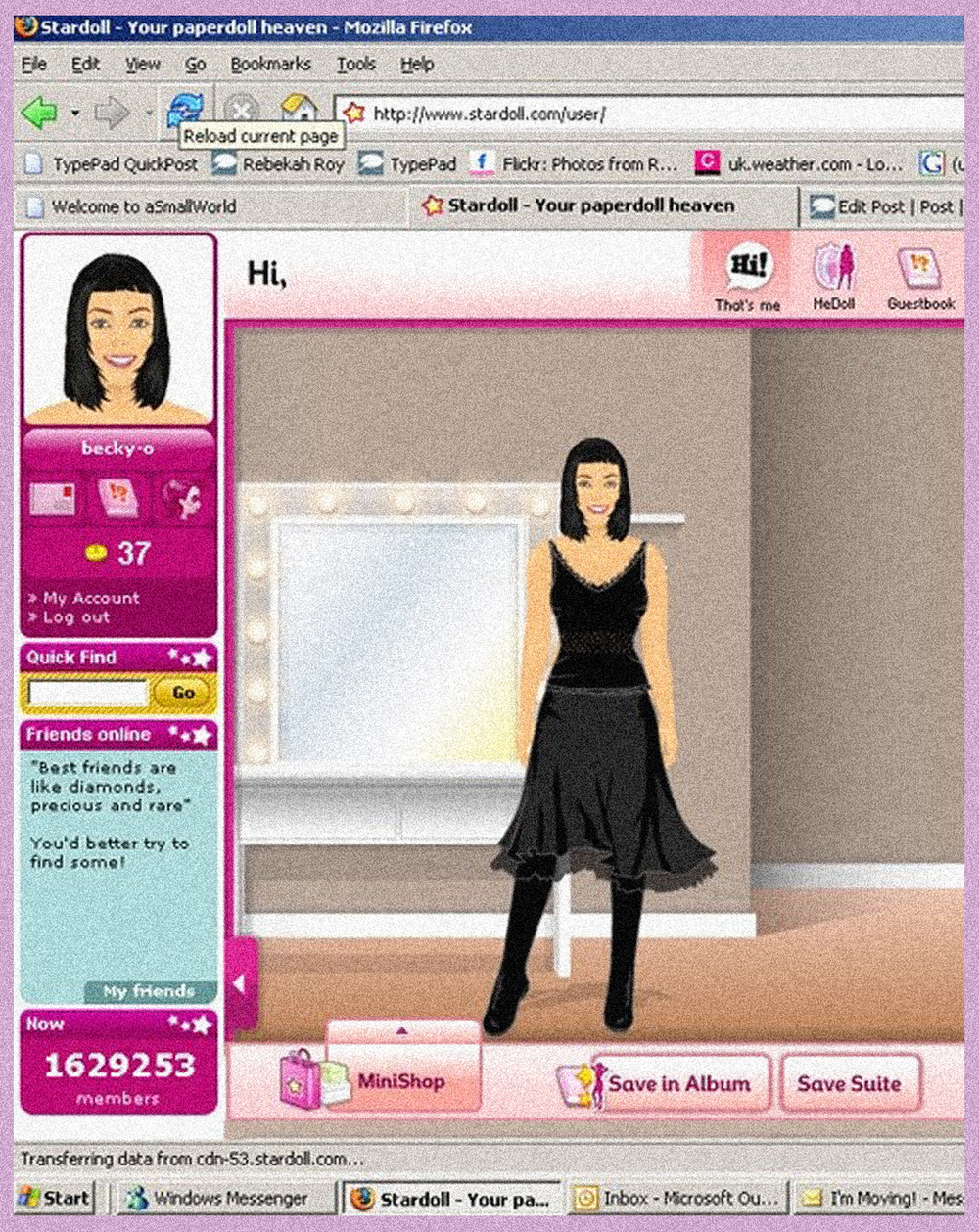

Unsure of what to make of these results, I close all my current tabs, open a new incognito window and google ‘Stardoll’ for the first time in ten years. I don’t interrogate the unconscious, robotic action that led me to make sure I was doing this in a private window, possibly still carrying my teenage shame despite now having a much more compromising search history. I’m glad to see the domain still exists and that the game has barely changed in the last decade. As I gleefully browse this buggy and outdated site, I bask in warm nostalgia and gratitude. At peace with the fact I’ll never truly know the role the game played in my succeeding queer journey, I’m grateful for this platform which allowed me to try out the ugliest outfit combinations of the 00s and lean into a - yet untapped - femininity when I really needed to.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Stardoll (‘Paperdoll Heaven’ when I first discovered it) is advertised as a ‘Dress Up Game for Girls’: a description I both actively and unconsciously refrained from thinking too deeply about in my adolescence. I first found out about the site through my older sister in the mid-2000s; I remember watching her with the corner of my eye dragging Bjork's iconic swan dress to cover her doll’s naked body on our family computer. I was immediately mesmerised.

The game has two main strands of play. On one side, it allows you to dress up celebrities - from Kelis to Camilla Parker Bowles - in both real and made-up outfits. On the other, it lets you create your own doll, giving you mini-missions with the purpose of building a fashion-forward wardrobe. When I was questioned by the only friend I knew who played the game on why I chose a girl-doll instead of a boy-doll, I decided to stop playing with the doll-sonas -and pretended that was the end of my relationship with Stardoll. In reality, I decided to focus solely on styling the celebrity dolls, maintaining a comfortable degree of distance from my personhood.

Having never built up the courage to directly ask my family to buy me a doll in my childhood, Stardoll allowed me to lean into that desire in safety at a later stage. For my barely prepubescent, somewhat friendless and pretty hobbyless self, the website would end up becoming a crucial companion for a good part of the next decade. Whilst most of my peers spent their unmonitored access to the internet watching porn, I - as well as doing that - also spent it coming up with dramatic storylines, competitions and imaginary fabulous scenarios for my dolls. I recorded information on an Excel spreadsheet and put more effort into it than I did in most other spheres of my life. Whilst the secrecy was liberating, it also meant this was a passion I never got to share with anyone else and an activity that only stayed within me.

Fast-forward ten years, my love for femininity is less of a secret as I welcomed my queerness and now spend my days dolling up and down and allow myself to attempt the ugliest outfit combinations in real life. All whilst surrounded by fellow queer people, many of whom had a somewhat similar journey to mine.

My friend Ve, who founded the video game-centred night SlayStation, also shares a love for Stardoll: “I discovered it because all the girls in my secondary school form group played it at lunch time.” She explains, “I started off just doing it jokingly like ‘haha look how silly I made her look’ - I think as a deflection of my enjoyment and defence of my ‘masculinity’.”

This deflection is similar to what 20 year old artist Sam Asher did when they first saw the girls in their school playing online doll dress up games: “I’d ask (in a coy, almost negging way) ‘What even is that?’ when really I was desperate to get stuck into it myself. I went home and stayed up hours into the night dressing my dolls in what I considered to be the most unique and interesting combinations of clothes.”

“Children, who are not yet institutionalised or subjected to ingrained capitalistic values, can hold gigantic potential for liberation of any sort; something as simple as the act of playing, for no purpose but enjoyment and discovery, could still be a powerful weapon to oppressive systems.”

For my friend Inara, who faced a dolls-ban at six years old from her parents, dress-up games re-offered her a sense of agency: “You had some sort of power to make decisions, be it as chaotic as pairing a pink clutch with red heels.” She continues, “Dress up games allowed me my own (walk-in) closet, with the promise that one day, I’d have one too and I wouldn’t have to hide anything in it, not even myself.”

Dress up games are far from perfect: They are still guilty of prioritising the same beauty standards that can be found in mainstream dolls and in mainstream life. However, for queer kids like us, where play comes with a caveat set by masculinity and gender expectations, they can be a key component in uncovering and exploring ourselves.

As I was mindlessly scrolling through TikTok the other day I stopped at a trans girl who bought some dolls to play with her trans sister, in an effort to reconnect with the childhood they wish they’d had. Transitioning is often referred to as a second puberty but never seen as an opportunity to rediscover our child self. Children, who are not yet institutionalised or subjected to ingrained capitalistic values, can hold gigantic potential for liberation of any sort; something as simple as the act of playing, for no purpose but enjoyment and discovery, could still be a powerful weapon to oppressive systems. I hope playing with dolls brings just that.

Words: June Bellebono