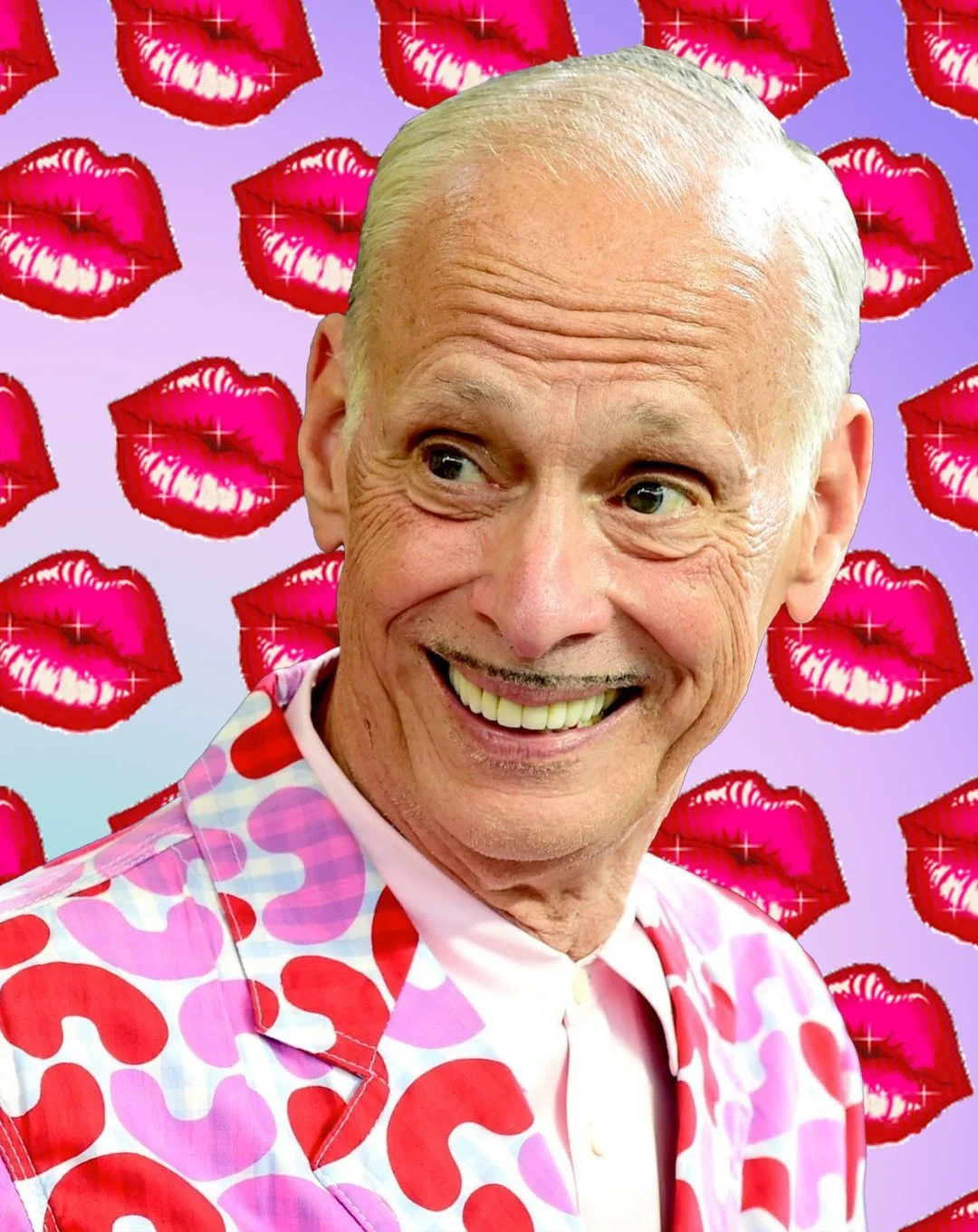

The (Bad) Taste Test: In Liarmouth, John Waters Tells a Twisted Truth

When it comes to John Waters, there’s always a temptation to fall back on describing and defining his work through shock value. After all, in their early collaborations together, Waters has Divine get sexually assaulted by a giant lobster in Multiple Maniacs; made monstrous and fried in the electric chair at the climax of Female Trouble; and, most (in)famously, has her eat dog shit in the final moments of Pink Flamingos. This final film is about Babs Johnson (Divine) on a quest to become the “filthiest person alive,” a title she resoundingly wins in that final, stomach-turning act of coprophagia.

The tagline for Pink Flamingos is “an exercise in poor taste,” the film then delivers on what feels almost like Waters playing the greatest hits of his early work; a wild collision of sex, violence, sin, and fetishism. But his work - both on film and otherwise - is much more than this list of inflammatory acts. And that’s where Liarmouth comes in.

Like with the films that came before it, it could be easy to list the most shocking elements of Liarmouth and end any discussion of it there. There’s pathological lying; a dog that “transitions” back and forth between being canine and being a cat; a cult of “bouncers”; and a queer, talking penis attached to a straight man. But to stop talking about it here does both the novel, and Waters, a disservice. Because, provocative as his work has always been, it’s (almost) always been in the service of something else. And in Liarmouth, this outrage exists as a vehicle for something that might seem surprising in its earnestness. As the subheading of the book - a feel-bad romance - suggests, Liarmouth is a kind of love story, but the irony is that in the end, it isn’t that much of a feel bad story at all.

Sure, it opens with Marsha Sprinkle stealing suitcases from unsuspecting families just landing from a flight, as she slips in and out of disguises, pathological lies, and then makes a getaway with her driver Daryl. Daryl is obsessed with her, and has taken as payment for his services, the promise that, once a year, he and Marsha will have sex. But Marsha - in a way that might seem like a contradiction compared to Waters’ past protagonists - hates the very idea of sex, of anything that’s messy or unclean. So she knows that she’ll have kicked Daryl to the curb long before he comes to collect. The two of them are separated early on in the novel, after a botched theft, and it becomes increasingly clear that the love story the book promised isn’t between these two mismatched souls at all.

Instead, Marsha meets a dogcatcher on a plane who ends up understanding her more than anyone else. He calls her “Liarmouth” and she ends up falling into his embrace. Waters asks: “can two damaged people become one?” And as the story unfolds, it becomes increasingly clear that he wants the answer to this question to be yes.

Everyone in the world of Liarmouth is damaged, a damage that often comes across like a kind of repression. From Marsha’s relationship to sex, to the way that she only eats crackers so that her trips to the bathroom are simply “pellets” (Divine would be devastated). The same is true of Daryl, the driver who spends the start of the book obsessed with Marsha, single-mindedly thinking of what it will be like to finally get to have sex with her. But after the two of them are wrenched apart, and Daryl receives a brutal injury between his legs, he ends up confronting part of himself he never thought would be disagree with him: his dick. It starts talking, and ends up being called Richard. And Richard, unlike the rest of Daryl, is queer.

“As with all of his work, Liarmouth is driven by a heart more than anything else, a desire to offer something up to people who are drifting outside of the outsiders, and welcoming them home. “

A lot of the comedy in Liarmouth plays like a kind of live-action cartoon, something that Waters wouldn’t be able to do on film; from talking dicks to the body horror inflicted on dogs for the hyper-rich by Marsha’s mother. There’s plenty of shock and outrage for people who come to Waters as a way to see what kind of buttons he’s pressing on his latest endeavour. But here, he’s more interested in looking inward, satirising outsiders as much as the majority. From the cult of “bouncers,” travelling vertically wherever they go, led by Marsha’s daughter; to the climactic pride parade for “rimmers" in the novel’s final act. A parade led by Marsha’s ex-husband; the shock and shame loaded into the idea that she “married a rimmer.” Some of these ideas feel like a continuation of A Dirty Shame; the last feature film that Waters directed, released in 2004. Here, Waters is still driven by the idea of what liberation can look like; but rather than being liberated from an oppressor - as is the case in something like his most political film, Desperate Living (1977) - these are characters who need to be liberated from themselves. Whether it’s Marsha finding truth where she’s only known lies, or the fraught relationship that Daryl has with Richard and his own sexuality, Liarmouth is, ironically, about the truth more than anything else.

There’s outrage everywhere in Liarmouth, often coming from the characters; whether it’s Marsha and her rimmer ex-husband, or the prejudice that Poppy feels are projected towards her cult of bouncers. But even more than some of Waters films, the Baltimore - and America more broadly - of Liarmouth one seemingly built by and for these outsiders. Waters has often described his films for being for minorities who don’t fit in with their own minority group, and this is what drives so much of Liarmouth forward. The queerness is bizarre; the one trans character is Surprize, the dog/cat owned by Marsha’s mother, described explicitly as a “transitioning animal.” But none of these feels played for shock, or as an attempt by Waters to punch down on trans people. As with all of his work, Liarmouth is driven by a heart more than anything else, a desire to offer something up to people who are drifting outside of the outsiders, and welcoming them home.

Words: Sam Moore