The Extraterrestrial World of Xenofeminism

I was having a heavily Merlot-fuelled discussion with a group of friends last year when one of them brought up the term ‘xenofeminism’. Having considered myself a feminist by specific standards, I was a mixture of confused and embarrassed that I had never heard this term before. “What exactly is xenofeminism?” I asked, probing into a completely unknown area. After the bottle was finished, with the promised follow-up of links and book suggestions, I suddenly discovered a different world of conversations among feminists. As I was curious to find out more, I realised that it’s important to share what I found.

What exactly is xenofeminism? What does it mean? And how does it fit into broader discussions of feminist ideology?

What is xenofeminism?

The images that came to mind when thinking about the term xenofeminism sat somewhere between the visuals of Katy Perry’s 2010 hit ‘E.T’ and Xena the Warrior Princess. What I found instead were definitions that went beyond the normal scope of understanding gender.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

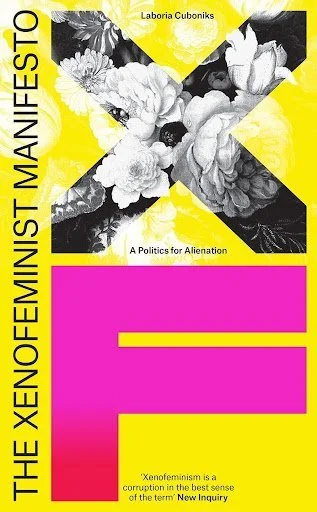

Xenofeminism is about transcending beyond our nature-based understanding of gender, using technology to abolish the concept of gender altogether. The prefix itself ‘xeno’ by definition means “other, different in origin”. According to the Xenofeminist Manifesto created by a cyber-feminist collective called Laboria Cuboniks, this way of viewing gender equality represents those that have been deemed ‘unnatural’, those that fall on the periphery of societal standards according to the supposed natural order of the world. By utilising technology to innovatively express progressive gender politics that include the theoretical and political thinking of women, queers and the gender non-conforming. One could also argue that xenofeminism is the new-age version of earlier ideas on cyberfeminism and technofeminism, both of which originated between the late-1990s and early 2000s and advocated for the inclusion of women into the social mechanisms that generate and programme technological advances.

“If there was a collective agreement on what progressive feminism looks like, there would be a larger consensus on how to fight oppressive structures.”

To consider it radical would be an understatement. Xenofeminism is asking us to take our idea of gender further, to abolish gendered labels and terminology related to it. For example, the Manifesto’s section titled ‘Trap’, highlights that the world views contemporary queer and feminist politics as a “plural but static constellation of gender identities, in whose bleak light equations of the good and the natural are stubbornly restored.” By putting non-conforming gender identities through the lens of our world’s understanding of what is ‘good’ and ‘natural’, it still centres on heteronormativity and the frameworks used to define our lives. Xenofeminism defines itself as ‘gender-abolitionist’ and aims to construct a society where the traits currently assembled under the rubric of gender, no longer being a function of asymmetric operation of power.

I won’t lie, the rest of the website describes xenofeminism through rigorously challenging academic jargon that is difficult to understand. But the crux of this ideology rests on the idea that everything we know about gender needs to be disregarded in place of a new technological, universalised reality that “cuts across race, ability, economic standing, and geographic position.”

The critiques and counter-arguments

With everything that’s been said, there are also analytical points that are against propelling xenofeminism as the theory of the future. One such critique is the privilege that scholars in the West (Europe, the US) afford when theorising about a future detached from different realities. For many people, identifying with a collective that recognises oppression due to their race, gender, and/or abilities forms the basis of real communal action, and not idealised, theoretical activism. On top of this, academia and its ideas about creating change often further the gap between theory and practice, without any concrete solutions to creating long-lasting social change. Furthermore, advocating for technology as the medium to create said social change is a paradox on its own. How can technological frameworks be the path to freedom when foundational aspects of technology have been inherently oppressive? Examples of this can be seen in hyper-surveillance, the effects on mental health and racist ideas influencing AI programmes.

So what now? How is this relevant to me?

Now more than ever, the global conversations on feminism are about making what was kept in books and behind fancy terms accessible to everyone. But in the process of making knowledge accessible, how do we make feminisms like xenofeminism part of our bigger conversations?

Xenofeminism’s ideas about the future are not far off from the developments we see in technology today, as many were predicted in pop culture and media depictions of futurism. The term Metaverse, for example, was popularised by a 1992 novel called Snowcrash, which predicted a world that is similar to what we see today (featuring smartphones, GPS, crypto-currency and the gig economy). As a result, our relationship to ideas like feminism will not only evolve but be deeply affected by the technologies and artificial worlds we create. And xenofeminism already recognises this as a futuristic way to live, by creating new institutions that centre on technomaterialism as the foundation for its construction. So maybe by 4050, xenofeminism in hindsight will be what set the basis for understanding the construction of gender in a material, hyper-technocratic society? Yet, in the face of the problems the world is facing currently, xenofeminism is a way of thinking about gender that feels like a hypothetical dream. Climate change deepened social-economic inequality, higher costs of living and increased right-wing political power across the globe tell us that our feminism needs to be vigilant in what we advocate for. Practising feminism solely through intellectual frameworks can prevent us from being in a community with others. In my opinion, the idea of being alienated whilst also being in a community through an intersectional lens is something that would be the main barrier to applying xenofeminist ideals in our everyday lives.

At the end of the day, despite the degree to which we think our ideas are progressive, empowerment looks different for each person. If there was a collective agreement on what progressive feminism looks like, there would be a larger consensus on how to fight oppressive structures. Yet, it is important to educate ourselves with the different tools and information that exist, so we can adapt and take what works for us. When it comes to understanding and applying xenofeminism in my own life? Like with any new flavour to add to a meal, I’ll take it with just a pinch.

Ijeoma Opara is a PhD student in Gender Studies, looking at expressions of black postfeminist identity in post-apartheid South Africa. If she’s not doing research, she’s freelance writing, DJing, or drinking red wine contemplating the meaning of it all.

References: The Xenofeminist Manifesto | Boyce Kay, J., 2019. Xenofeminism | Braidotti R. 1996. Cyberfeminism with a difference. New Formations, 29: 9-25 | Heft, P. 2021. Xenofeminism: A Framework to Hack the Human. Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry, 21(1): 121-139 | Mackenzie, A. 2020. Review of Helen Hester (2018). Xenofeminism. Political Science and Education, 3: 634-640 | Puente, S. N. 2008. From cyberfeminism to technofeminism: From an essentialist perspective to social cyberfeminism in cedrtain feminist practives in Spain. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31: 434-440.