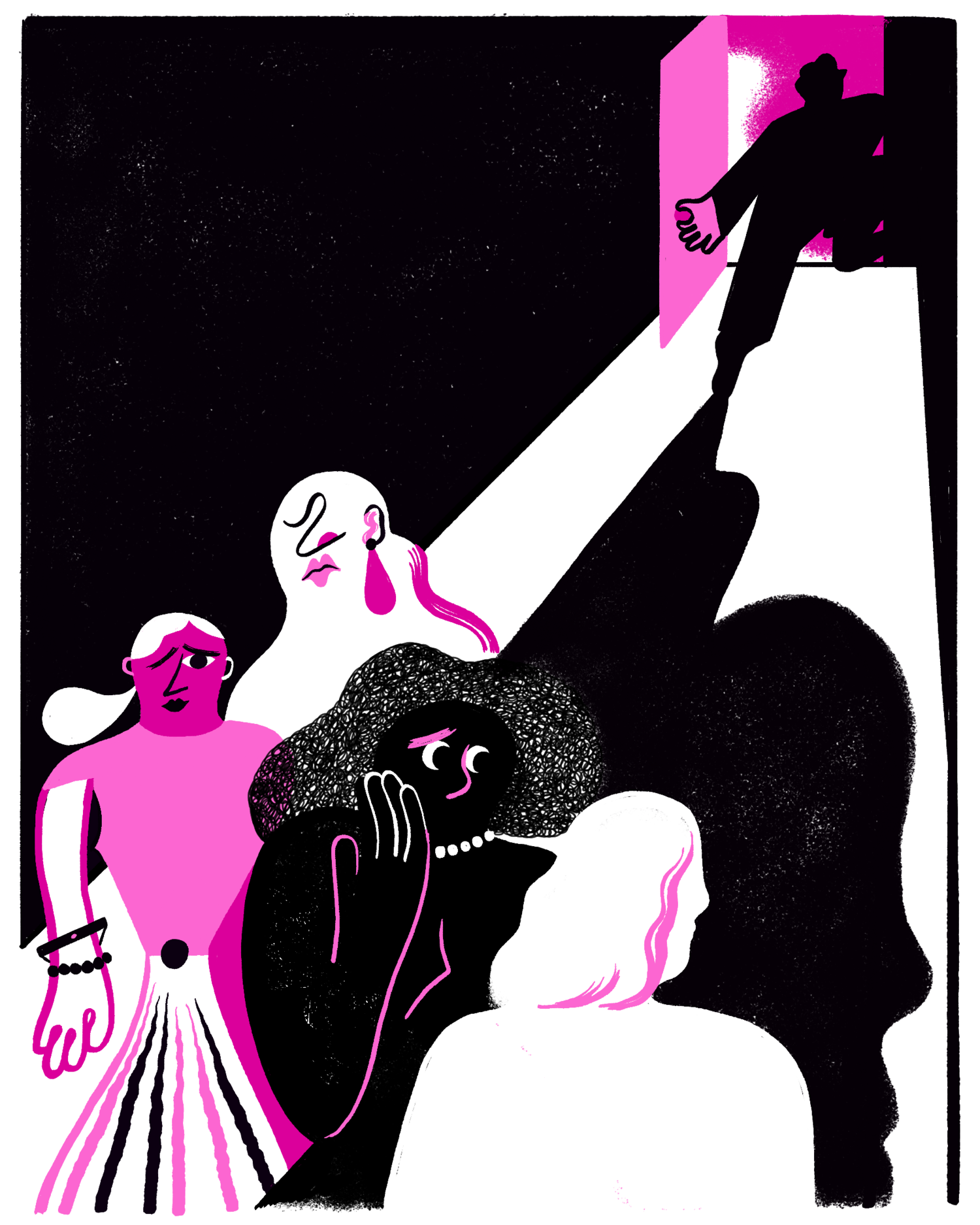

The Investigation: On Gendered Violence, Injustice & True Crime

When I told my sister that I was watching The Investigation, the BBC’s latest instalment of Scandi-noir, she glanced scathingly over at me: ‘another one where a woman’s murdered and a team of male policemen search for her violated body?’

Yeah, I guess she’s right.

Directed by Tobias Lindholm, the series is a slow-paced true crime drama closely based on the case for the murder of 30-year-old Swedish journalist Kim Wall. The media attention in the wake of her 2017 disappearance was extreme.

By the end of that year, over 60,000 articles had been written worldwide about the horrific circumstances of her death – the largest homemade submarine in the world, the dismemberment, the pieces of her body being dredged from the ocean over the following months.

By 2020, this number eclipsed 100,000. I think of Olivia Gatwood’s poem, ‘Murder of a Little Beauty’, comprised of lines from People’s magazine’s 1997 coverage of the murder of JonBenet Ramsey (‘rope & a blanket found near the victim/the blood & flesh of Miss Virginia West’).

We know how this kind of reporting plays out: Wall was rarely the focus of the journalism generated by her death - the perpetrator was. A grim fascination around him and the twisted mechanics of the killing act itself, again and again, demarcated Wall as ‘victim’. The majority of contemporary true crime is obsessed with the psyche, life, methods, and motivations of killers rather than the victims of their grand, notorious crimes.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

This sensationalism is perhaps most prominently visible surrounding Ted Bundy, grotesquely heralded for his intelligence across numerous documentaries. However, society’s cacospectamania – obsession with viewing the repulsive – far extends him. The Investigation received acclaim for its effort to buck trends of romanticising the killer alongside the grim allure of a gory aesthetic, with reviewers arguing it ‘eschewed gruesome shocks for patient, humane drama’.

The series is, in a sense, atypical of the true crime genre; Wall’s murderer isn’t named once. Lindholm, openly shunning what he calls the ‘media circus’ response to Wall’s death, writes that he attempted to make ‘a story where we didn’t even need to name the perpetrator’, one which was ‘simply not about him.’ Wall’s family - as well as the team involved in the case - were consulted during the show’s production and pleased with the finished product.

Her parents, determined to remain in control of their daughter’s narrative, wrote that ‘if anyone will write Kim’s story, it will be us, and no one else.’ Their dog, Iso, plays himself in the drama, marking The Investigation’s wider project being concerned with staying as true to the family’s reality as possible.

But why is the bar so low for ‘humane’ true crime storytelling?

Yes, The Investigation handles the murder relatively sensitively by not showing explicit images, liaising with the victim’s family, candidly showing the brutal nature of their grief, and allowing Wall’s journalistic legacy screen time. But surely these kinds of considerations should be a given when cinematising the murder of a young woman, and not a ‘radical’ deviation from the norm?

I am reminded of Cassandra Troyan’s poetry collection, Freedom & Prostitution, which considers how some people slot more neatly into the category of ‘victim.’ Sex workers defy victim status as dominant social discourse dictates they were ‘asking for it.’ Often it is black, brown, and trans women who vanish at the hands of violence without the social outrage or investigations that their white siblings who fall victim to similar fates receive.

Wall’s body is somehow simultaneously absent from and horribly present in The Investigation. We are never shown her corpse; the closest we get to an image is a line drawing of her torso shown to her parents.

However, entire episodes centre around divers searching for pieces of her – severed legs, arms, head – discarded and weighed down in plastic bags on the seafloor. The cinematography is gaping, monochrome, bleak as the situation it depicts. We see plastic bags brought to the surface, we see the clinical environment of the forensics department where they end up, but never the body itself, a conspicuous absence that generates its own distinct horror. What is more terrifying than being reduced to a collection of composite body parts, becoming a limbless torso?

Director Lindholm wrote in The Guardian that the series ‘could talk about society and a justice system that actually works, rather than humanising the perpetrator’. The irony in this is that Lindholm doesn’t seem to consider that the The Investigation’s drama hinges on the fact that there’s a strong chance that the murderer won’t be convicted.

The show – seemingly unwittingly – demonstrates the absurdly high standard of evidence beyond reasonable doubt required to convict a crime of this nature. Despite the perpetrator changing his story not once, not twice, but three times whilst in custody (in his final account of events admitting to decapitating Wall but continuing to paint the incident as an accident), the prosecutor still didn’t have enough ‘hard’ evidence to take the case to court.

What is clearly meant to be a testament to the police’s dedication and stamina in the case, for me, sheds light on the petty bureaucracy and, if anything, injustice of the criminal justice system from police station through to court. Freedom of Information requests made by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in 2018 showed that, over a three-year period, police officers accused of domestic abuse were a third less likely to be convicted than members of the general public facing the same accusations.

This is not a system built for, or working in favour of, survivors.

Sure, the murderer was apprehended in this instance. But we are repeatedly reminded of how difficult it was to convict someone for even this most brutal act – the notion that he could’ve got away with it hangs like a bad smell even after the resolution.

In her book Feminism, Interrupted, Lola Olufemi argues against the prison industrial complex, observing that though we have been ‘taught about police and the court system being vehicles for justice’, the material reality of the state that organises them, as well as the systemic racism of these bodies, results in an aggregate of harm to minority groups.

In the forward to her poetry collection Life of the party: If a girl screams, and other poems, Olivia Gatwood relays this argument with regard to the true crime genre:

I want the stories that honor girls, not sensationalize them. The true crime I want knows that over half of the women murdered worldwide are killed by their partners or family members. The true crime I want does not celebrate police or prison as a final act of justice, but recognizes these systems as perpetrators too—defective, corrupt, and complicit in the same violence that they prosecute.

A critique of this sort often generates more questions than it answers – how do we tell stories of violence whilst simultaneously keeping victims alive in a way that doesn’t glorify or mythologise the circumstances of their deaths? Who are these narratives even for?

If the police don’t protect minorities, how can we imaginatively organise alternative systems that do? In her book, Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed writes that ‘feminist consciousness can be thought of as consciousness of the violence and power concealed under the language of civility.’

One of the closing lines of The Investigation sees the prosecutor note that ‘the more civilised we become, the greater is our need to stare into darkness.’ Ahmed notices how this very language of ‘civilisation’ masks that the darkness has always been there.

Words: Marina Scott | Illustrations: Franz Lang