Traces Of Us: Lesbian Letter Writing and Odes in Art

Words: Bree Turner

Make it stand out

We started with books — Dostoevsky for her, Miranda July for me. She told me she’s an artist, and I told her I write. Our messages became an exchange of our work and lives: her art, my words. Before we met, she sent me a photo of the cliffs in Étretat, where she had been travelling. Later, I saw a Boudin painting of Étretat in a gallery in Madrid and sent it to her. We were mapping ourselves onto each other, connecting through what we created and what we saw.

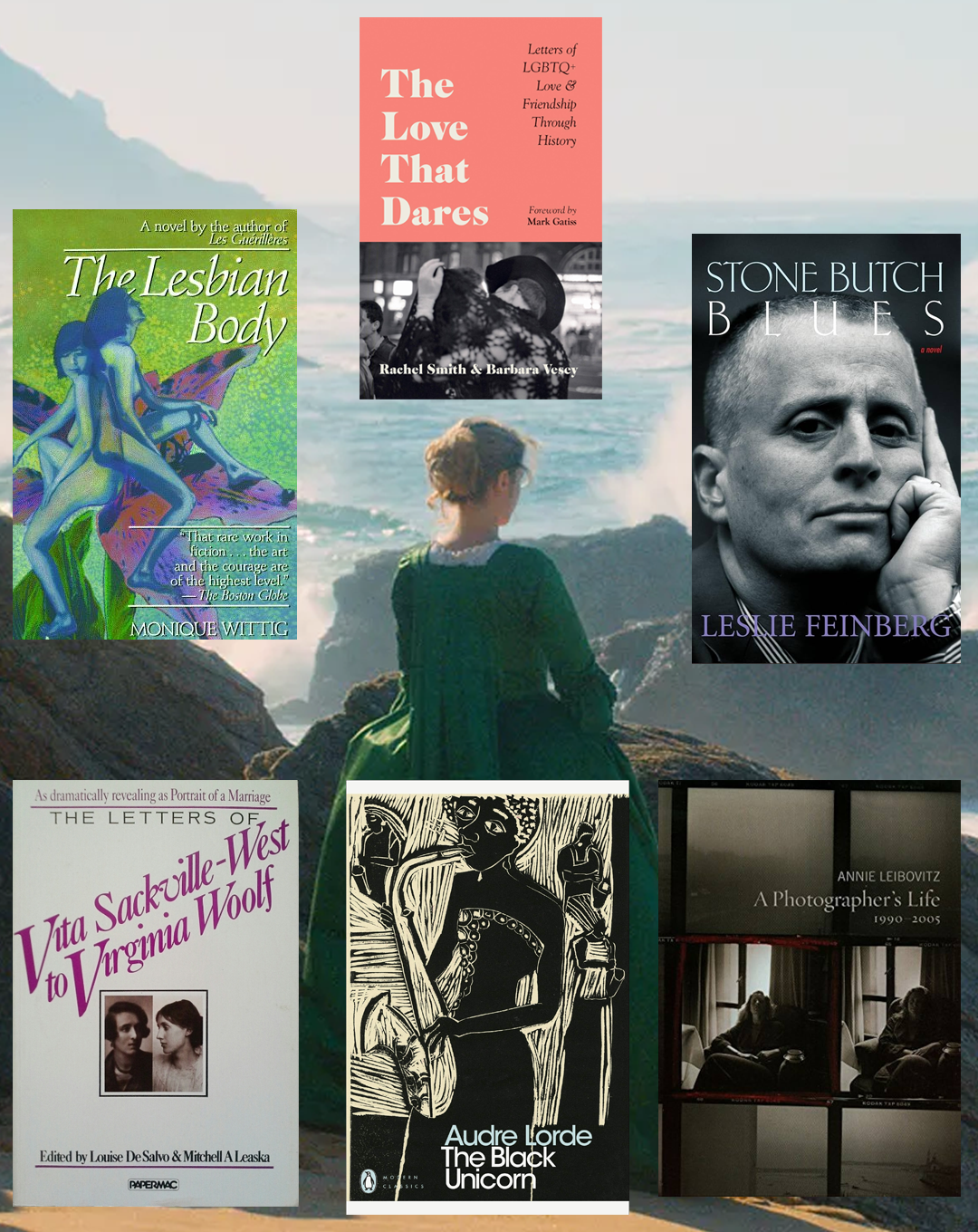

She told me once that Art requires an address, a tether to something real. Over the course of our time together, we addressed many things to one another: handwritten letters, poetry, photos and paintings. Before we ended, she took my portrait—an intimate act of preservation. The photos arrived in my mailbox with a note A visual trace of the moment we shared. I wrote back, enclosing a photo I had taken of her, a Susan Sontag quote, and a copy of Stone Butch Blues. She had asked what colour my weeks had been since we last saw each other. I told her to read the book if she wanted to know. Leslie Feinberg’s seminal novel, Stone Butch Blues, begins with a letter. We ended with one.

Letter writing or odes in art between lesbians are testament to elliptical love throughout history. Letters serve as a vessel for what cannot be said aloud. Rachel Smith and Barbara Vesey’s book The Love That Dares documents centuries of LGBTQ+ correspondence — letters that persisted despite secrecy. These messages bear witness to connections that often could not exist openly, yet left indelible marks on those who wrote them. Scholar and author, Dr Pamela VanHaitsma, refers to this as epistolary rhetoric and considers letters indispensable sources for the development of LGBTQ+ histories, studies of public memory, and research on communication.

Sappho stands as a popular and primary reference for lesbian poetry, her fragmented verses carrying the weight of desire, devotion, and the female voice in love. Across centuries, her words have been a point of return—attestation to the ways lesbian longing has always sought expression. In The Lesbian Body (1986), Monique Wittig directly addresses Sappho, invoking her not just as a poet but as an ancestor, a figure through whom the lineage of lesbian love and language is traced. Wittig’s novel itself functions as a love letter, both to the lesbian body and to the literary traditions that have sought to name and honor it. In her visceral, fragmented prose, she reclaims the body from silence and erasure, much like Sappho did in her time, forging an address that spans history, desire, and the written word.

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West wrote to one another for eighteen years (1923-1941). Their correspondence revealed the unique alchemy that existed between two great writers, their devotion to each other, and how they inspired one another creatively. Sackville-West, called herself “the thing that wants Virginia”, revealing her vulnerability and desire. Woolf, less elusive in her letters than her reputation suggests wrote “I’m settling down to wanting you, doggedly, dismally, faithfully”, demonstrating how letters allow the author to reveal more of themselves on the page.

In 1977, writer Audre Lorde met visual artist Mildred Thompson at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture in Nigeria, where Thompson was exhibiting work. The two had a brief intimate relationship through 1978. Their unfinished Journey Stones sketchbook combined Thompson’s drawings with ten poems by Lorde, including Timepiece, later published in The Black Unicorn (1978). Though unpublished, it remains archival proof of what they shared.

“These messages bear witness to connections that often could not exist openly, yet left indelible marks on those who wrote them.”

Susan Sontag and Annie Leibovitz were romantically involved for fifteen years (1989–2004), though it was never publicly acknowledged. After Sontag’s death, Leibovitz’s A Photographer’s Life, 1990–2005 documented their years together. Leibovitz admitted in the book that “words like 'companion' and 'partner' were not in our vocabulary, we were two people who helped each other through our lives. The closest word is still 'friend'." Through the photographs we can see evidence of that life, their travels, their apartments in Paris and New York — a disclosure of their intimacy.

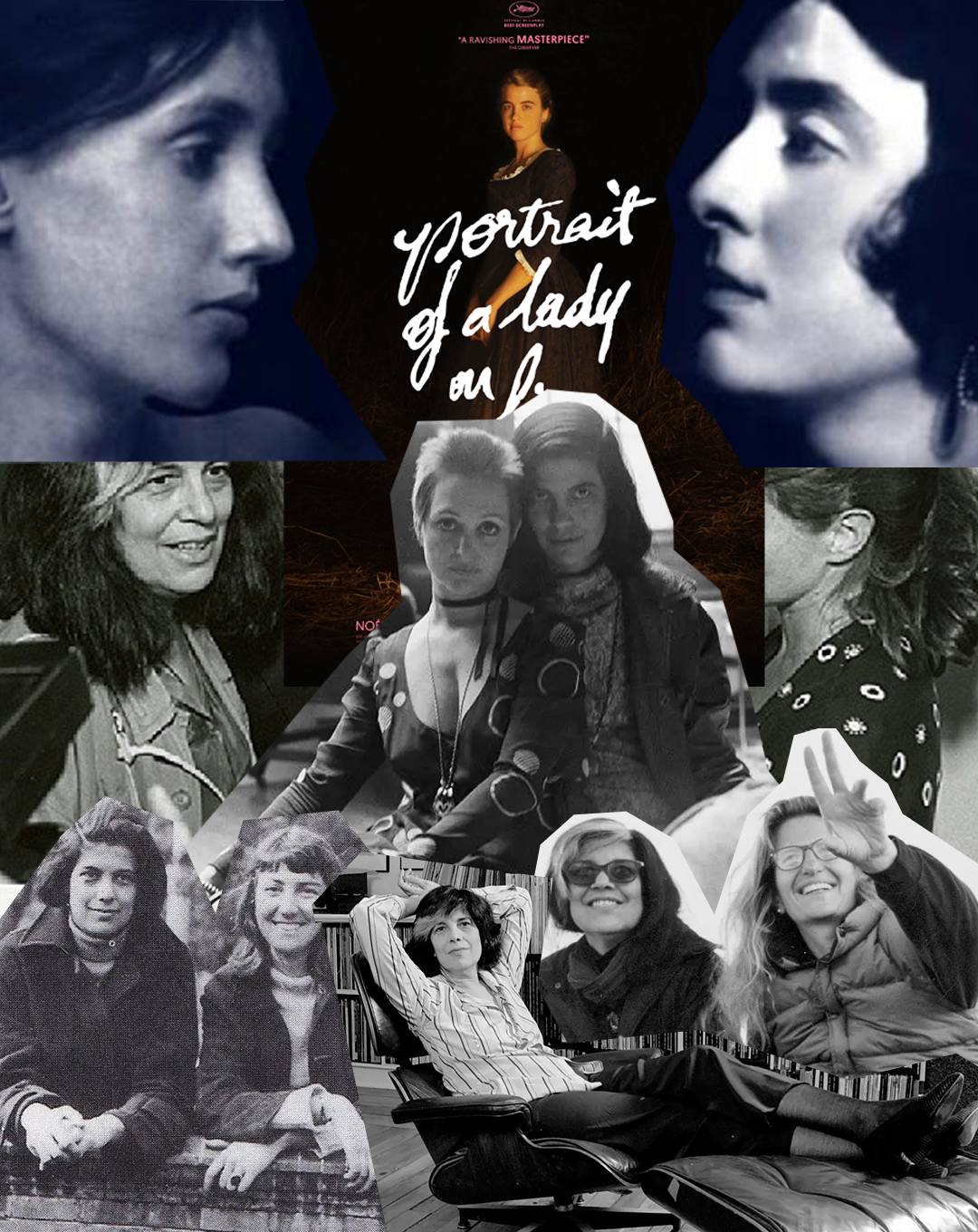

Representations of letter writing and odes in art dominate the queer literature and film I love. In Chloe Michelle Howarth’s book Sunburn, the two central characters Lucy and Susannah write to one another, chronicling their secret and forbidden love in regional Ireland in the 1990s. In the film Carol, Therese is both released and summoned by Carol through letters. In Blue is the Warmest Colour, Adele serves as muse to Emma in her paintings, and in The Incredibly True Adventure of Two Girls in Love, the girls exchange letters, music and poetry. They read passages from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which is referenced throughout the film and offers a comparison for queer love in literature.

In Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Héloïse’s final act of love is not a verbal declaration but a memory in a portrait. Marianne sees the portrait of Héloïse years after their affair - in the painting Héloïse is seen parting the pages of a book slightly with her finger, revealing the number twenty eight, immortalizing their bond in art. Viewers will recall that page twenty eight of the book Héloïse is holding in the portrait contained a sketched nude of Marianne.

Today, we can speak to people across distances with ease, our words flickering across screens, instant, ephemeral and endless. Yet something lingers in the act of writing to one person with intention, in addressing them directly. For queer love, so often shaped by absence, displacement, and longing, letters and odes in art offer a kind of permanence — a way of saying we were here. Even now, I find myself writing to her (or us) in these words, preserving what we were. Because love, elliptical or not, always requires an address.