Why Are So Many New Books Feminist Retellings of Greek Myths?

Take a walk through a bookshop today and you will most likely notice the ever-increasing collection of Greek mythology retellings that are littering the shelves. Titles like A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes, Ariadne by Jennifer Saint, or The Women of Troy by Pat Barker are some of the feminist takes on these classic stories, and among the bestsellers in a genre that appears to be ever-growing. However, more and more readers are starting to voice frustration at what is beginning to feel like an over-saturation of mythology retellings in the book market.

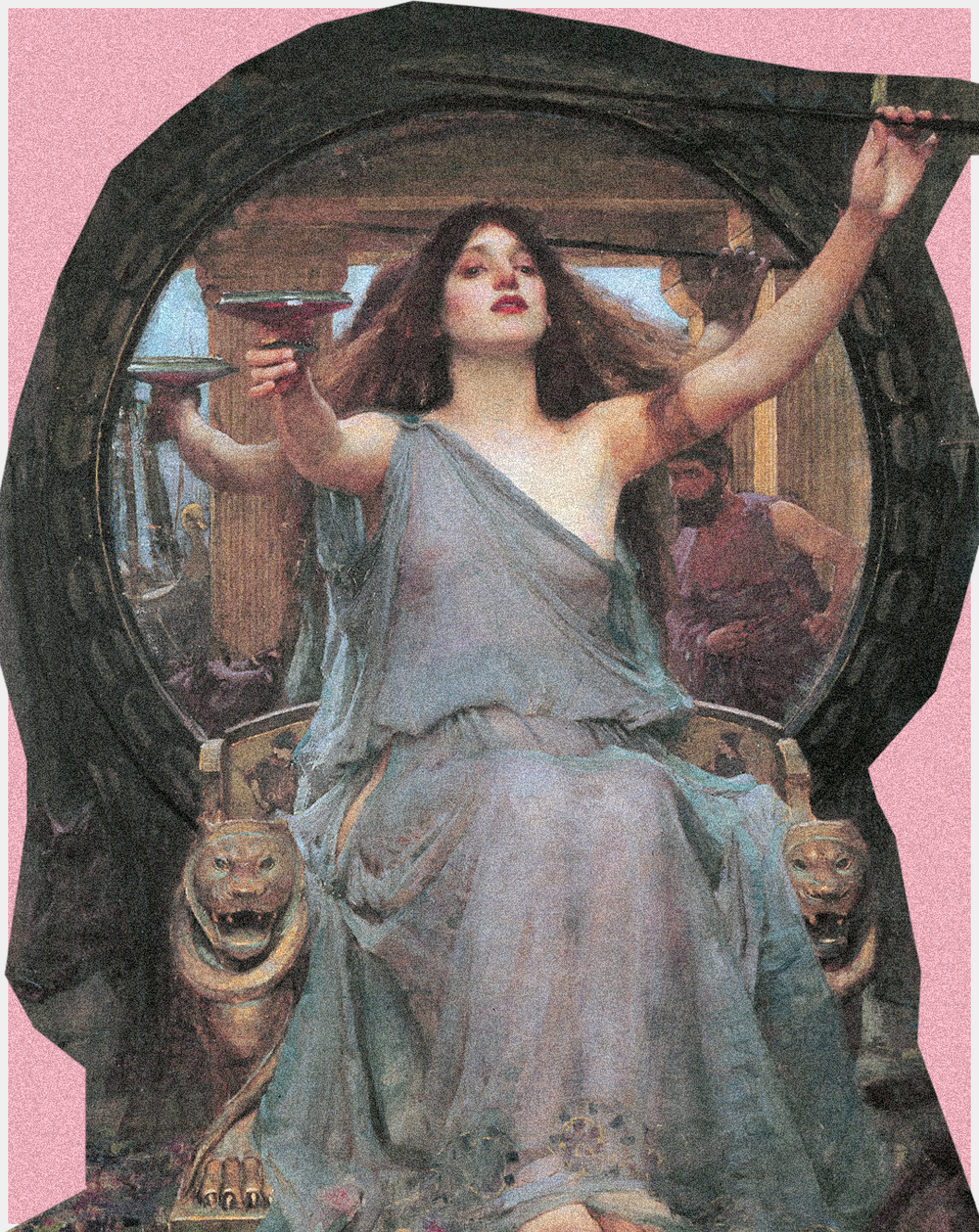

Madeline Miller’s Circe, the eagerly awaited follow-up to her wildly successful The Song of Achilles, retelling the story of the witch Circe who features all too briefly in The Odyssey by Homer, arguably started this trend in publishing. And I say trend in publishing, not writing, for a reason. Retellings of classic stories, particularly Greek myth in this case, have always happened. Ursula K LeGuin published Lavinia in 2008 (although this is based on Roman rather than Greek mythology), Margaret Atwood The Penelopiad in 2005, and Christa Wolf released Medea in 1996. Hell, James Joyce wrote Ulysses in 1920 and Shakespeare wrote Troilus and Cressida in 1602. This is not a new genre, and for good reason - these stories are captivating, exciting, and have characters that have stood the test of millennia. But this recent move from publishers to relentlessly push these retold narratives is starting to grate.

Many are starting to voice tiredness at this genre’s proliferation on the shelves, suggesting it’s the girl-bossification of Greek myth and joking that they are waiting for the “misogynist” mythology retellings to shake things up a bit; although perhaps we only need to look back in time to find those. While out-and-out criticism of the genre seems a little harsh, after all these are mostly stories about women, by women (often debut authors) and the only other place to see these characters are in thousand-year-old texts with questionable gender politics in both the texts themselves and from those who translated them.

However, that doesn’t mean that everyone complaining about this topic are bitter female misogynists or snobbish academics. It’s genuinely disconcerting to see one type of book be pushed beyond all others. It draws attention to the fickle market forces at play in publishing, a space we too often like to think of as sacred and immune to the sway of capital (even as it remains one of the most financially brutal industries). It also emphasises what we have always known: that a story’s success is measured by how marketable it is. There’s a thousand years of evidence to suggest these stories will sell, and this is on top of the recent interest in the past five years evidenced through the various titles that have made their way to the top of bestseller lists, with over half of those appearing on various literary prize shortlists, such as Goodreads’ Choice Award, Women’s Prize for Fiction, and Costa Book Award, since 2017. It forces us to remove our rose-tinted glasses through which we often view publishing.

This is all especially galling when feminism or ‘feminist retellings’ are the thing being so relentlessly monetised. It is pandering to women by the publishing industry, but not the writers – I want to be clear on that. Publishers have found something that appeals to the feminist zeitgeist and are running with it, taking topics that should be liberatory, like feminism and women’s writing, and instead shrinking its possibilities down to a narrow range of stories. These books even all look the same, with bafflingly similar cover art which at times feels like an attempt to dupe readers into purchasing the wrong book - muddling their Medusa with their Medea and leave them coming back for more.

A large part of the suspicion around these retellings is the frustration around their repetitive nature, particularly with the whiteness and euro-centricity that much of the mythology publishing gravitates towards. While yes, centring women in these stories might differ from their original form, these are still the myths that many of us grew up learning about in school, reading in children’s encyclopaedias, and watching the Disney adaptations of. So how revolutionary are they really if these stories feed into the whitewashing of Greek myth and still largely marginalise the stories of women of colour? In this way the retelling trend veers dangerously close to the white feminism trap, offering a narrow and superficial kind of representation that only serves to liberate one kind of woman.

However, the good news is, as a result of this genre’s popularity, we are slowly starting to see a lot more retellings of myths from beyond the Greek, Roman and Norse mythology we have come to expect. Titles such as Bolu Babalola’s Love in Colour which explores mythology from around the world through short love stories, Axie Oh’s Korean folktale retelling The Girl Who Fell Beneath the Sea, and Vaishnavi Patel’s Kaikeyi which retells part of the Sanskrit Ramayana epic. So, if you are tired of Helen of Troy and Persephone there is so much more mythology out there to explore.

So, why are retellings supposedly better or more commercially viable than new stories? Should we keep rehashing these old stories, circling around these same tropes and tales rather than expanding outwards into new perspectives and writers?

It’s debatable - are these retellings not new stories in themselves? The very nature of them, and why they are so popular today, is that they are telling a story - a woman’s story - that was historically side-lined in the original text and presents a fresh narrative. Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, for all its problems, does tell the story of those we never truly hear from in The Iliad. Also, while there are some big names in the retelling genre, with Pat Barker, Jennifer Saint, Natalie Haynes and Claire Heywood having written multiple bestsellers, there are many debut female authors writing in this genre whose novels are received much more widely than they might have been if mythology retellings weren’t en vogue - writers like Luna MacNamara whose Psyche and Eros releases later this year, or Laura Shepperson whose novel Phaedra also comes out in a few months.

“A story built on a formula that is guaranteed to bring in the big bucks to those in the production studios and publishing houses behind them.”

On the flip-side, are authors choosing to write mythology retellings to try and cheat the publishing odds? This claim is a tad harsh and ignoring the fact that publishing is deeply subject to trends and that, yes, writers need to pay rent too. It’s easy to understand readers’ frustration and cynicism towards the publishing industry. If you know or follow any aspiring writers on social media you’ll see how publishing really can be a numbers game which doesn’t reward everyone’s stories equally.

However, knowing what we do about how difficult it is to get taken seriously in the industry, why should we disparage writers who are using their skills in a way that would see them more likely to make money? Yes, these books might not be to your taste, you might find the genre played-out or even cringe, but there is no shortage of readers who love these novels, who find them insightful, beautifully written, and important despite the popularity that causes others to disregard them. There seems to be this idea that true creativity lives outside of trends, that an artist forfeits some of their respect if they ‘give in’ to market demands. But why is this the case? Why is it seen as suspicious when writers, who are majority women in this case, find a formula for monetary success?

Ultimately, it all seems similar to the fatigue many people feel towards the sheer amount of Marvel films and TV series. Yes, they may be entertaining and fun - they may even showcase stories and actors from marginalised communities, bringing them to huge audiences – however, they are still by-and-large only telling a certain kind of story. A story built on a formula that is guaranteed to bring in the big bucks to those in the production studios and publishing houses behind them.

Words: Natalie Wall